Федеральное государственное учреждение «Государственный Эрмитаж», музей изобразительного и декоративно-прикладного искусства, расположенный в комплексе Зимнего дворца центра города Санкт-Петербург. Один из крупнейших и значимых художественных и исторических музеев мира. Свою историю начал с частной коллекции произведений искусства, приобретённых Императрицей Екатериной II. Первоначально собрание размещалось в дворцовом флигеле — Эрмитаже, откуда и закрепилось общее название будущего музея. До середины XIX века Эрмитаж соответствовал своему названию Ermitage — уединённое место, посещать музей могли лишь избранные.

Современный Государственный Эрмитаж представляет собой сложный музейный комплекс. Основная экспозиционная часть музея занимает 5 зданий, расположенных вдоль набережной реки Невы, главным из которых принято считать Зимний дворец, также музею принадлежат Восточное крыло Главного штаба на Дворцовой площади, Меншиковский дворец, фондохранилище в Старой Деревне и другие здания. Коллекция музея насчитывает около трёх миллионов произведений искусства и памятников мировой культуры, начиная с каменного века и до нашего столетия.

Руководство Государственного Эрмитажа

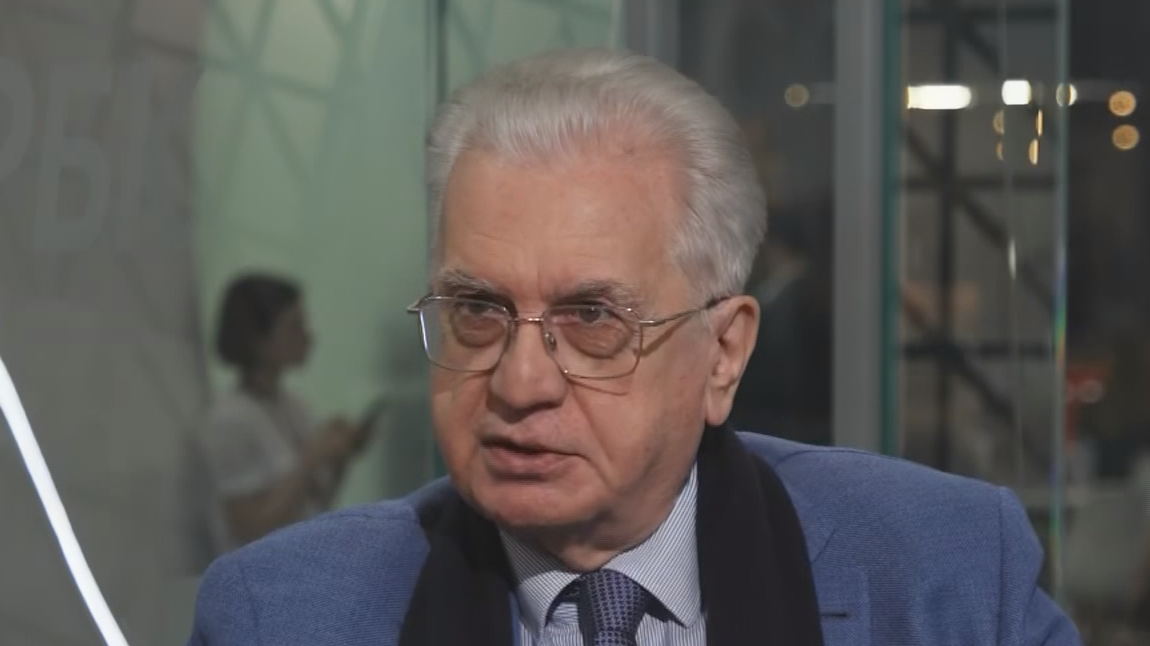

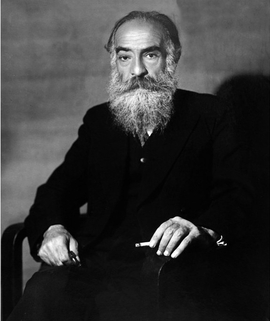

Пиотровский Михаил Борисович — Генеральный директор Государственного Эрмитажа

Вилинбахов Георгий Вадимович

Заместитель генерального директора по научной работе, Государственный герольдмейстер Российской Федерации, профессор Санкт-Петербургской государственной художественно-промышленной академии имени А. Л. Штиглица, доктор исторических наук

Адаксина Светлана Борисовна

Заместитель генерального директора, главный хранитель

Антипова Марина Владимировна

Заместитель генерального директора по финансово-плановой работе

Богданов Алексей Валентинович

Заместитель генерального директора по эксплуатации, кандидат технических наук, доцент Санкт-Петербургского университета Государственной противопожарной службы

Попечительский совет Государственного Эрмитажа

Потанин Владимир Олегович

Президент компании «Интеррос», председатель Попечительского совета

Авдеев Александр Алексеевич

Посол РФ в Ватикане

Блаватник Леонид Валентинович

Президент компании «Access Industries»

Греф Герман Оскарович

Президент, председатель Правления ОАО «Сбербанк России»

Дерипаска Олег Владимирович

Генеральный директор ОАО «Базовый элемент»

Кудрин Алексей Леонидович

Декан факультета свободных искусств и наук СПбГУ

Пьер де Лабушер

Любимов Юрий Сергеевич

Статс-секретарь — заместитель Министра юстиции Российской Федерации

Пиотровский Михаил Борисович

Генеральный директор Государственного Эрмитажа

Силуанов Антон Германович

Министр финансов Российской Федерации

Акимов Андрей Игоревич

Председатель Правления ОАО «Газпромбанк»

Фридлянд Леонид Яковлевич

Президент компании «Меркурий»

Швыдкой Михаил Ефимович

Специальный представитель президента РФ по международному культурному сотрудничеству

Дин Гилфиллан

Генеральный директор JTI Россия

Якобашвили Давид Михайлович

Вице-президент Российского союза промышленников и предпринимателей

25 ноября 2019 года Российский музей «Эрмитаж» подписал соглашение с сирийским Управлением культурного наследия и музеев о сотрудничестве в реставрации памятников Пальмиры, планируется издание книги о том, как пальмирские памятники оказались в РФ. С сирийской стороны подписал соглашение директор DGAM Махмуд Хаммуд. Перед подписанием соглашения Пиотровский, арабист по образованию, прочитал в музее лекцию об Эрмитаже на арабском языке. Пиотровский и Хаммуд также открыли фотовыставку «Две Пальмиры» о сирийском городе и Санкт-Петербурге.

16 ноября 2019 года государственный Эрмитаж представил в зале Леонардо да Винчи картину Сандро Боттичелли «Мадонна делла Лоджиа» из коллекции Галереи Уффици, написанная в 1467 году. Вместе с ней в зале выставлена греческая икона «Богоматерь с младенцем Элиуса», которая относиться к этому же стилю. Изучить полотно смогут незрячие и слабовидящие люди, для них выставят тактильную копию картины и предоставят информацию с помощью аудиогида.

12 ноября 1917 года народный комиссар просвещения Анатолий Васильевич Луначарский объявил Зимний дворец и Эрмитаж государственными музеями. Царская резиденция открыла свои двери не только придворным особам, а всем желающим. В новое учреждение поступили художественные произведения из императорских дворцов столицы и пригородных резиденций — Гатчины, Петергофа и Царского села, а также дворцов петербургской знати. Кроме того, фонды Эрмитажа пополнились коллекцией Академии художеств и училища технического рисования барона Штиглица.

17 февраля 1852 года В Санкт-Петербурге, при участии Императора Николая I, состоялось открытие Публичного музея, Нового Эрмитажа, одного из пяти связанных друг с другом зданий на Дворцовой набережной. Здания были построены специально для этой цели, по проекту баварского архитектора Лео фон Кленце. Тогда уже музей представлял богатейшие коллекции памятников древневосточной, античной и средневековой культур, искусства Западной и Восточной Европы.

11 февраля 1764 года Начал свою историю Императорский Эрмитаж как частная художественная коллекция Екатерины II, после того как в Берлине она приобрела у коммерсанта Иоганна Эрнеста Гоцковского коллекцию из 225 работ голландских и фламандских художников, общей стоимостью в 183 тысячи талеров, в счёт его долга, возникшего из-за неудачной поставки зерна русской армии, при участии князя Владимира Сергеевича Долгорукова. Поначалу великие картины размещались в апартаментах дворца, получивших первоначальное название Императорский Эрмитаж.

«Фонтанка» — петербургская интернет-газета, где можно найти не только новости Петербурга, но и последние новости дня, и все важное и интересное, что происходит в России и в мире. Здесь вы отыщете наиболее значимые происшествия, новости Санкт-Петербурга, последние новости бизнеса, а также события в обществе, культуре, искусстве. Политика и власть, бизнес и недвижимость, дороги и автомобили, финансы и работа, город и развлечения — вот только некоторые из тем, которые освещает ведущее петербургское сетевое общественно-политическое издание. Санкт-Петербург читает «Фонтанку»! Наша аудитория — лидеры бизнеса и политики, чиновники, десятки тысяч горожан.

- Пользовательское соглашение

- Политика конфиденциальности

- Правила использования материалов сайта

- Политика использования cookies

За два с половиной века своей истории Эрмитажем руководили 19 человек. Директорами крупнейшей сокровищницы искусства нашей страны становились люди с разными взглядами и способностями, но почти всех их объединяет стремление сохранить национальное достояние и приумножить уникальные коллекции. Мы расскажем о самых масштабных личностях, внесших наиболее заметный вклад в развитие главного музея страны.

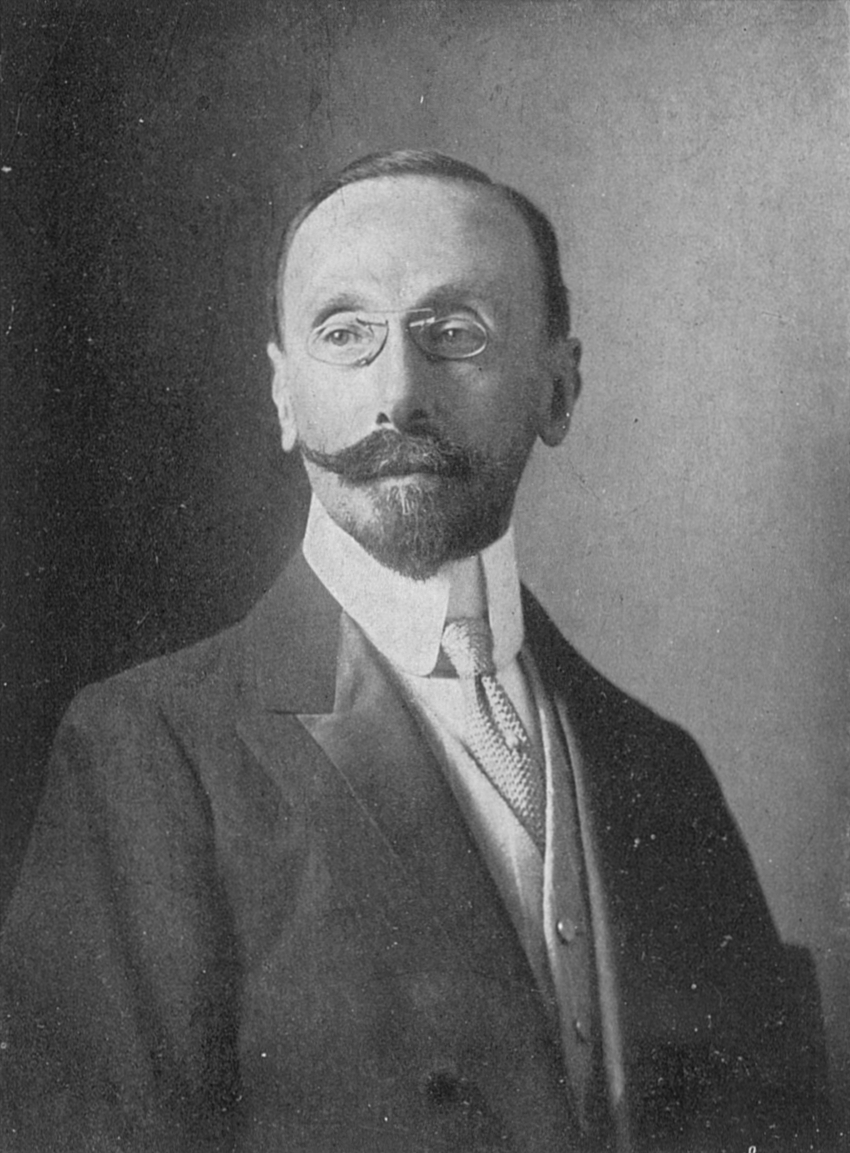

Первый директор. Степан Гедеонов (1863-1878)

Русский историк, драматург, искусствовед Степан Александрович Гедеонов — первый директор Императорского Эрмитажа.

Прежде всего директор занялся изданием каталога картин. Вслед за этим под его кураторством появился каталог галереи древней скульптуры. А через год вышло уже созданное им самим новое издание — сначала на французском языке, а еще через год — на русском.

Степан Гедеонов первым предложил расширить круг посетителей, упростив процедуру посещения музея. До этого в Эрмитаж пускали лишь в вицмундирах или фраках, по особым входным билетам, выдававшимся Придворной Конторой. А уж разрешение на снятие копии с какой-нибудь картины получали с еще большими проволочками. По этой причине визитеров в Эрмитаже было мало. Директор не без труда добился, чтобы публику впускали безо всяких билетов и в обычных костюмах.

На своем посту Степан Александрович особое значение придавал археологическим памятникам и продолжал расширять коллекции Эрмитажа. В 1865 году он побывал в Милане и в Париже, где на аукционе купил для музея немало ценных вещей. Среди них — «Мадонна Литта» Леонардо да Винчи. Спустя два года он отправился за новыми экспонатами в Лондон. Всего стараниями Гедеонова Императорский Эрмитаж стал обладателем около 800 ценных предметов — ваз, бронз, мраморов и 9 картин.

Остроумно пополнял коллекции. Александр Васильчиков (1879-1889)

В 1885-м в Париже по инициативе Васильчикова было куплено собрание произведений прикладного искусства эпохи Средневековья и Возрождения. Приобретение послужило толчком для образования в музее нового отделения. Одновременно Эрмитаж обогатился собранием оружия из арсенала Царского Села.

Во время директорства Васильчикова здесь начали работать выдающиеся ученые: египтолог Голенищев, археолог Кизерицкий, составивший рукописный каталог собрания Отделения древностей. А также знаток Византии Кондаков, историк Сомов, возглавивший в 1886 году картинную галерею. К 25-летнему юбилею царствования Александра II под руководством Васильчикова издается книга «Императорский Эрмитаж, 1855-1880».

Неудобный для новой власти. Дмитрий Толстой (1909-1918)

Работе на этих двух позициях он посвящал себя полностью — чуть ли не круглосуточно находился в музеях, а отдыхать позволял себе лишь пару летних месяцев в году.

Годы войны Толстой провел в Петрограде, в нем же встретил обе революции. Даже в те тяжелые времена он, по воспоминаниям современников, оставался честным чиновником и способствовал сохранению музейных сокровищ, не позволяя их продавать или дарить. Однако крупные государственные и политические перемены внесли в культурную жизнь страны свои коррективы — людей старой закалки с высоких должностей начинают снимать.

В конце 1918 года Толстой, не подавая в отставку, получает разрешение советских властей на отпуск и уезжает в Киев. Дорога выдалась трудной — она проходила через Москву, там графа едва не задержали. Однако обошлось, и вскоре он оказался в Киеве, где к тому времени уже находилась его семья. Узнав о расстреле великих князей в Петропавловской крепости (конец января 1919 г. — Ред.), Толстой принял окончательное решение: в Петроград не возвращаться, с властями не сотрудничать. Таким образом и закончилась его работа в должности директора Эрмитажа.

Экспонаты над умывальником. Иван Всеволожский (1899-1909)

В 1881-1899 годах он — директор Императорских театров и прямой подчиненный министра двора. Обладал широчайшим кругозором и массой регалий: русский театральный и музейный деятель, сценарист, художник служил тайным советником и обер-гофмейстером.

В 1899 году Всеволожский занял пост директора Эрмитажа. Имея связи за границей, он хорошо понимал, какое значение для всего мира имеет этот музей — к тому времени его залы уже были полны редчайшими произведениями искусства.

Всеволожский сумел провести большую разноплановую работу, которая вывела музей на новый этап существования. Так, серьезные изменения коснулись документирования музейной деятельности. В 1908 году была поставлена задача проведения инвентаризации во всех отделах и составлен подробный план работ с использованием существовавшей на тот момент описи экспонатов. Учетные работы осложнялись тем, что в то время в Эрмитаже не существовало единого реестра хранящихся в нем предметов.

Такой объемный и сложный труд, к сожалению, послужил тому, что приобретения того времени были невелики и фонды государственной сокровищницы искусства обновлялись хаотично. Самым значительным пополнением коллекции того периода можно назвать подарок сотрудника музея Голенищева, передавшего 38 античных предметов и ценную библиотеку из 848 томов.

Известный оперный певец Богомир Корсов вспоминал о деятельности Ивана Всеволожского так: «Он обратил внимание на иностранную живопись и пополнил коллекцию Эрмитажа массой хороших картин… многие думали, что это картины покупные.

А меж тем Всеволожский находил их в забытых, заброшенных помещениях старых дворцов, в Петербурге, в Петергофе, Екатерингофе, которые по многу лет оставались незанятыми в ожидании случайных высоких гостей, иногда украшали стены над умывальниками, принимая на себя брызги умывающихся».

2 апреля 1906 года министр двора, барон Фредерикс объявил ему Высочайшую благодарность, вручив портрет императора и знак «За отличную беспорочную службу за пятьдесят лет». Деятельность Всеволожского на посту директора Эрмитажа была высоко оценена.

Музейный хранитель. Сергей Тройницкий (1918-1927)

Сергей Николаевич положил начало изучению и научному описанию собрания отдела прикладного искусства.

В июне 1920 года в Эрмитаже открывается факультет музейного дела, где читают курс лекций, программу для которого разрабатывает комиссия, в состав которой входит Тройницкий. В то же время в Эрмитаже организуется и Музей придворного быта. Ставя для себя приоритетом сохранение и приумножение музейной коллекции, всю свою деятельность директор направил на сохранение национального достояния страны. 29 октября 1922 года им организована Галерея серебра (нынешний зал майолики) и им же написан путеводитель по ней.

Но и в судьбе Сергея Николаевича политическая воля сыграла роковую роль: Тройницкий сначала был смещен с поста директора, а потом и вовсе снят с работы с запрещением занимать административно-руководящие должности. Это было прописано в постановлении Ленинградской областной комиссии Рабоче-крестьянской инспекции по чистке государственного аппарата. Дело в том, что ученый неоднократно выступал против навязываемой сверху распродажи сокровищ Эрмитажа. Его арестовали 28 февраля 1935 года как «социально опасный элемент» и сослали в Уфу.

Всю блокаду провел в Ленинграде. Иосиф Орбели (1934-1951)

Орбели, востоковед с мировым именем, пришел в Эрмитаж летом 1920-го.

В 1946-м Орбели выступил на Нюрнбергском трибунале свидетелем обстрелов города на Неве. Рассказал о руинах Петергофа, Пушкина, Павловска. О том, что немцы прицельно бомбили Эрмитаж. Адвокат, защищавший гитлеровских генералов, попробовал оспорить его показания. Мол, свидетель — не артиллерист. Как же он может говорить о преднамеренности обстрелов?

«Я никогда не был артиллеристом. Но в Эрмитаж попало тридцать снарядов, а в расположенный рядом мост всего один, и я могу с уверенностью судить, куда целил фашизм. В этих пределах я артиллерист!» — ответил Орбели.

Прекрасный организатор, он сделал все, чтобы после войны быстро восстановить экспозицию. Уже в октябре 1945-го 69 залов открылись для посетителей. В дальнейшем под руководством Орбели Эрмитаж стал подлинно народным музеем. Каким остается и до сих пор.

Умер на работе. Михаил Артамонов (1951-1964)

Его отличала принципиальность, в том числе по острым вопросам. При его поддержке в Эрмитаже была организована выставка Пикассо, удалось сохранить творения импрессионистов. В период «оттепели» он помог вернувшимся из заключения ученым — Гумилеву, Латынину, Спасскому. Его увольнение тоже связано со скандалом.

В 1964-м Артамонов принял на работу студентов, отчисленных из Академии художеств за приверженность к абстрактному искусству, и оформил их такелажниками. А затем разрешил бунтарям, среди которых были впоследствии широко известные Шемякин, Овчинников, Уфлянд, показать в Эрмитаже свои работы. Экспозицию закрыли через полтора дня, но она успела войти в историю мировой живописи XX века как «выставка такелажников». Еще через пару дней отстранили и строптивого директора. Затем он плодотворно трудился на историческом факультете ЛГУ.

Умер прямо за рабочим столом, редактируя статью.

«Сторож» великого музея. Борис Пиотровский (1964-1990)

В Эрмитаже Борис Пиотровский начал работать в 1931-м, сначала в должности младшего научного сотрудника. Однако уже через несколько лет он блестяще защищает диссертацию и заявляет о себе как выдающийся ученый. Великая Отечественная застала его в очередной научной командировке в Закавказье. Он мог там остаться, но вернулся в Ленинград. Самое тяжелое блокадное время, зиму 1941-1942 годов, Пиотровский провел вместе со своими сотрудниками. Занимался эвакуацией ценностей, сохранением сокровищ. Ни одно произведение искусства за это время не было повреждено. Затем Пиотровский вместе с другими специалистами эвакуировался в Ереван. Туда же отправились более двух млн уникальных произведений разных эпох. В Армении сотрудники Эрмитажа и коллекции пробыли до осени 1944 года.

В этом же году в стенах научной академии Борис Борисович защитил докторскую, а темой его научных трудов стали история и культура древней цивилизации Урарту. В 1964-м он назначается директором Эрмитажа, в этой должности проработал 25 лет. Ученый в шутку нередко говорил, что является «сторожем» самого крупного в стране музея. Сегодня в здании на Дворцовой набережной воссоздан его кабинет, там все как при жизни академика. Так что ходит легенда, что он по-прежнему «охраняет» Эрмитаж.

На посту — 27 лет. Михаил Пиотровский (1992 — наши дни)

Сегодня это знаковая для города и всей мировой культуры фигура. Он много делает, чтобы на благо Эрмитажа работали самые передовые технологии, а с его сокровищами могли познакомиться как можно больше людей. Не случайно филиалы музея открыты в Казани, Омске, Амстердаме, Выборге и Екатеринбурге. 9 декабря Михаилу Пиотровскому исполнилось 75 лет.

«Свой день рождения я не праздную и всегда провожу в Эрмитаже, — признался директор. — Считаю, что это самое большое счастье».

Смотрите также:

- Профессия – «эрмитажник». Как работают сотрудники крупнейшего музея России →

- Неизвестный Эрмитаж. 7 интересных фактов о главном музее Петербурга →

- Жизнь в музее. Как Борис Пиотровский стал хранителем Эрмитажа →

|

|

View of (from left) the Hermitage Theatre, Old Hermitage, and Small Hermitage |

|

Interactive fullscreen map |

|

| Established | 1764; 259 years ago |

|---|---|

| Location | 34 Palace Embankment, Dvortsovy Municipal Okrug, Central District, Saint Petersburg, Russia |

| Collection size | 3 million[1] |

| Visitors | 2,812,913 visitors (2022)[2] |

| Director | Mikhail Piotrovsky |

| Public transit access | Admiralteyskaya station |

| Website | hermitagemuseum |

The State Hermitage Museum (Russian: Государственный Эрмитаж, tr. Gosudarstvennyj Ermitaž, IPA: [ɡəsʊˈdarstvʲɪn(ː)ɨj ɪrmʲɪˈtaʂ]) is a museum of art and culture in Saint Petersburg, Russia. It was founded in 1764 when Empress Catherine the Great acquired a collection of paintings from the Berlin merchant Johann Ernst Gotzkowsky. The museum celebrates the anniversary of its founding each year on 7 December, Saint Catherine’s Day.[3] It has been open to the public since 1852. The Art Newspaper ranked the museum 10th in their list of the most visited art museums, with 2,812,913 visitors in 2022.[4]

Its collections, of which only a small part is on permanent display, comprise over three million items (the numismatic collection accounts for about one-third of them).[5] The collections occupy a large complex of six historic buildings along Palace Embankment, including the Winter Palace, a former residence of Russian emperors. Apart from them, the Menshikov Palace, Museum of Porcelain, Storage Facility at Staraya Derevnya, and the eastern wing of the General Staff Building are also part of the museum. The museum has several exhibition centers abroad. The Hermitage is a federal state property. Since July 1992, the director of the museum has been Mikhail Piotrovsky.[6]

Of the six buildings in the main museum complex, five—namely the Winter Palace, Small Hermitage, Old Hermitage, New Hermitage, and Hermitage Theatre—are all open to the public. The entrance ticket for foreign tourists costs more than the fee paid by citizens of Russia and Belarus. However, entrance is free of charge the third Thursday of every month for all visitors, and free daily for students and children. The museum is closed on Mondays. The entrance for individual visitors is located in the Winter Palace, accessible from the Courtyard.

Etymology[edit]

A hermitage is the dwelling of a hermit or recluse. The word derives from Old French hermit, ermit «hermit, recluse», from Late Latin eremita, from Greek eremites, that means «people who live alone», which is in turn derived from ἐρημός (erēmos), «desert».

Buildings[edit]

Originally, the only building housing the collection was the «Small Hermitage». Today, the Hermitage Museum encompasses many buildings on the Palace Embankment and its neighbourhoods. Apart from the Small Hermitage, the museum now also includes the «Old Hermitage» (also called «Large Hermitage»), the «New Hermitage», the «Hermitage Theatre», and the «Winter Palace», the former main residence of the Russian tsars. In recent years, the Hermitage has expanded to the General Staff Building on the Palace Square facing the Winter Palace, and the Menshikov Palace.[7]

Collections[edit]

The Western European Art collection includes European paintings, sculpture, and applied art from the 13th to the 20th centuries.

Egyptian antiquities[edit]

Since 1940, the Egyptian collection, dating back to 1852 and including the former Castiglione Collection, has occupied a large hall on the ground floor in the eastern part of the Winter Palace.

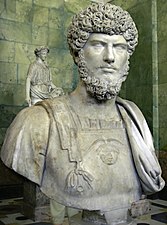

Classical antiquities[edit]

The collection of classical antiquities occupies most of the ground floor of the Old and New Hermitage buildings. The interiors of the ground floor were designed by German architect Leo von Klenze in the Greek revival style in the early 1850s, using painted polished stucco and columns of natural marble and granite.

The Room of the Great Vase in the western wing features the 2.57 m (8.4 ft) high Kolyvan Vase, weighing 19 t (42,000 lb), made of jasper in 1843 and installed before the walls were erected. While the western wing was designed for exhibitions, the rooms on the ground floor in the eastern wing of the New Hermitage, now also hosting exhibitions, were originally intended for libraries.

The collection of classical antiquities features Greek artifacts from the third millennium – fifth century BC, ancient Greek pottery, items from the Greek cities of the North Pontic Greek colonies, Hellenistic sculpture and jewellery, including engraved gems and cameos, such as the famous Gonzaga Cameo, Italic art from the 9th to second century BC, Roman marble and bronze sculpture and applied art from the first century BC — fourth century AD, including copies of Classical and Hellenistic Greek sculptures. One of the highlights of the collection is the Tauride Venus, which, according to latest research, is an original Hellenistic Greek sculpture rather than a Roman copy as it was thought before.[8] There are, however, only a few pieces of authentic Classical Greek sculpture and sepulchral monuments.

Prehistoric art[edit]

On the ground floor in the western wing of the Winter Palace the collections of prehistoric artifacts and the culture and art of the Caucasus are located, as well as the second treasure gallery. The prehistoric artifacts date from the Paleolithic to the Iron Age and were excavated all over Russia and other parts of the former Soviet Union and Russian Empire. Among them is a renowned collection of the art and culture of nomadic tribes of the Altai from Pazyryk and Bashadar sites, including the world’s oldest surviving knotted-pile carpet and a well-preserved wooden chariot, both from the 4th–3rd centuries BC. The Caucasian exhibition includes a collection of Urartu artifacts from Armenia and Western Armenia. Many of them were excavated at Teishebaini under the supervision of Boris Piotrovsky, former director of the Hermitage Museum.

Jewelry and decorative art[edit]

Four small rooms on the ground floor, enclosed in the middle of the New Hermitage between the room displaying Classical Antiquities, comprise the first treasure gallery, featuring western jewellery from the 4th millennium BC to the early 20th century AD. The second treasure gallery, located on the ground floor in the southwest corner of the Winter Palace, features jewellery from the Pontic steppes, Caucasus and Asia, in particular Scythian and Sarmatian gold.

Pavilion Hall, designed by Andrei Stackenschneider in 1858, occupies the first floor of the Northern Pavilion in the Small Hermitage. It features the 18th-century golden Peacock Clock by James Cox and a collection of mosaics. Two galleries spanning the west side of the Small Hermitage from the Northern to Southern Pavilion house an exhibition of Western European decorative and applied art from the 12th to 15th century and the fine art of the Low Countries from the 15th and 16th centuries.

Italian Renaissance[edit]

The rooms on the first floor of the Old Hermitage were designed by Andrei Stakenschneider in revival styles in between 1851 and 1860, although the design survives only in some of them. They feature works of Italian Renaissance artists, including Giorgione, Titian, Veronese, as well as Benois Madonna and Madonna Litta attributed to Leonardo da Vinci or his school.

The Italian Renaissance galleries continues in the eastern wing of the New Hermitage with paintings, sculpture, majolica and tapestry from Italy of the 15th–16th centuries, including Conestabile Madonna and Madonna with Beardless St. Joseph by Raphael.

Italian and Spanish fine art[edit]

The first floor of New Hermitage contains three large interior spaces in the center of the museum complex with red walls and lit from above by skylights. These are adorned with 19th-century Russian lapidary works and feature Italian and Spanish canvases of the 16th–18th centuries, including Veronese, Giambattista Pittoni, Tintoretto, Velázquez and Murillo.

Knights’ Hall[edit]

The Knights’ Hall, a large room in the eastern part of the New Hermitage originally designed in the Greek revival style for the display of coins, now hosts a collection of Western European arms and armour from the 15th–17th centuries, part of the Hermitage Arsenal collection.

The Gallery of the History of Ancient Painting adjoins the Knights’ Hall and also flanks the skylight rooms. It was designed by Leo von Klenze in the Greek revival style as a prelude to the museum and features neoclassical marble sculptures by Antonio Canova and his followers. In the middle, the gallery opens to the main staircase of the New Hermitage, which served as the entrance to the museum before the October Revolution of 1917, but is now closed.

Dutch Golden Age and Flemish Baroque[edit]

The rooms and galleries along the southern facade and in the western wing of the New Hermitage are now entirely devoted to Dutch Golden Age and Flemish Baroque painting of the 17th century, including the large collections of Van Dyck, Rubens and Rembrandt.

German, Swiss, British and French fine art[edit]

The first floor rooms on the southern facade of the Winter Palace are occupied by the collections of German fine art of the 16th century and French fine art of the 15th–18th centuries, including paintings by Poussin, Lorrain, Watteau. The collections of French decorative and applied art from the 17th–18th centuries and British applied and fine art from the 16th–19th century, including Thomas Gainsborough and Joshua Reynolds, are on display in nearby rooms facing the courtyard.

Russian art[edit]

The richly decorated interiors of the first floor of the Winter Palace on its eastern, northern and western sides are part of the Russian culture collection and host the exhibitions of Russian art from the 11th-19th centuries.

French Neoclassical, Impressionist, and post-Impressionist art[edit]

French Neoclassical, Impressionist and post-Impressionist art, including works by Renoir, Monet, Van Gogh and Gauguin, are displayed on the fourth floor of the Eastern Wing of the General Staff Building. Also displayed are paintings by Camille Pissarro (Boulevard Montmartre, Paris), Paul Cézanne (Mount Sainte-Victoire), Alfred Sisley, Henri Morel, and Degas.[9][10]

Modern, German Romantic and other 19th–20th century art[edit]

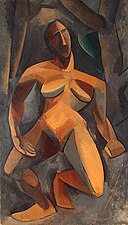

Modern art is displayed in the General Staff Building (Saint Petersburg). It features Matisse, Derain and other fauvists, Picasso, Malevich, Petrocelli, Kandinsky, Giacomo Manzù, Giorgio Morandi and Rockwell Kent. A large room is devoted to the German Romantic art of the 19th century, including several paintings by Caspar David Friedrich. The second floor of the Western wing features collections of the Oriental art (from China, India, Mongolia, Tibet, Central Asia, Byzantium and Near East).

History[edit]

Origins: Catherine’s collection[edit]

Catherine the Great started her art collection in 1764 by purchasing paintings from Berlin merchant Johann Ernst Gotzkowsky. He assembled the collection for Frederick II of Prussia, who ultimately refused to purchase it. Thus, Gotzkowsky provided 225 or 317 paintings (conflicting accounts list both numbers), mainly Flemish and Dutch, as well as others, including 90 not precisely identified, to the Russian crown.[11] The collection consisted of Rembrandt (13 paintings), Rubens (11 paintings), Jacob Jordaens (7 paintings), Anthony van Dyck (5 paintings), Paolo Veronese (5 paintings), Frans Hals (3 paintings, including Portrait of a Young Man with a Glove), Raphael (2 paintings), Holbein (2 paintings), Titian (1 painting), Jan Steen (The Idlers), Hendrik Goltzius, Dirck van Baburen, Hendrick van Balen and Gerrit van Honthorst.[12] Perhaps some of the most famous and notable artworks that were a part of Catherine’s original purchase from Gotzkowsky were Danaë, painted by Rembrandt in 1636; Descent from the Cross, painted by Rembrandt in 1624; and Portrait of a Young Man Holding a Glove, painted by Frans Hals in 1650. These paintings remain in the Hermitage collection today.[13]

In 1764, Catherine commissioned Yury Felten to build an extension on the east of the Winter Palace which he completed in 1766. Later it became the Southern Pavilion of the Small Hermitage. From 1767 to 1769, French architect Jean-Baptiste Vallin de la Mothe built the Northern Pavilion on the Neva embankment. Between 1767 and 1775, the extensions were connected by galleries, where Catherine put her collections.[14] The entire neoclassical building is now known as the Small Hermitage. During the time of Catherine, the Hermitage was not a public museum and few people were allowed to view its holdings. Jean-Baptiste Vallin de la Mothe also rebuilt rooms in the second story of the south-east corner block that was originally built for Elizabeth and later occupied by Peter III. The largest room in this particular apartment was the Audience Chamber (also called the Throne Hall) which consisted of 227 square meters.[13]

The Hermitage buildings served as a home and workplace for nearly a thousand people, including the Imperial family. In addition to this, they also served as an extravagant showplace for all kinds of Russian relics and displays of wealth prior to the art collections. Many events were held in these buildings including masquerades for the nobility, grand receptions and ceremonies for state and government officials. The «Hermitage complex» was a creation of Catherine’s that allowed all kinds of festivities to take place in the palace, the theatre and even the museum of the Hermitage. This helped solidify the Hermitage as not only a dwelling place for the Imperial family, but also as an important symbol and memorial to the imperial Russian state. Today, the palace and the museum are one and the same. In Catherine’s day, the Winter Palace served as a central part of what was called the Palace Square. The Palace Square served as St. Petersburg’s nerve center by linking it to all the city’s most important buildings. The presence of the Palace Square was extremely significant to the urban development of St. Petersburg, and while it became less of a nerve center later into the 20th century, its symbolic value was still very much preserved.[15]

Catherine acquired the best collections offered for sale by the heirs of prominent collectors. In 1769, she purchased Brühl’s collection, consisting of over 600 paintings and a vast number of prints and drawings, in Saxony. Three years later, she bought Crozat’s collection of paintings in France with the assistance of Denis Diderot. Next, in 1779, she acquired the collection of 198 paintings that once belonged to Robert Walpole in London followed by a collection of 119 paintings in Paris from Count Baudouin in 1781. Catherine’s favorite items to collect were believed to be engraved gems and cameos. At the inaugural exhibit of the Hermitage, opened by Charles, Prince of Wales in November 2000, there was an entire gallery devoted to representing and displaying Catherine’s favorite items. In this gallery her cameos are displayed along with cabinet made by David Roentgen, which holds her engraved gems. As the symbol of Minerva was frequently used and favored by Catherine to represent her patronage of the arts, a cameo of Catherine as Minerva is also displayed here. This particular cameo was created for her by her daughter-in-law, the Grand Duchess Maria Fyodorovna. This is only a small representation of Catherine’s vast collection of many antique and contemporary engraved gems and cameos.[16]

The collection soon overgrew the building. In her lifetime, Catherine acquired 4,000 paintings from the old masters, 38,000 books, 10,000 engraved gems, 10,000 drawings, 16,000 coins and medals, and a natural history collection filling two galleries,[17] so in 1771 she commissioned Yury Felten to build another major extension. The neoclassical building was completed in 1787 and has come to be known as the Large Hermitage or Old Hermitage. Catherine also gave the name of the Hermitage to her private theatre, built nearby between 1783 and 1787 by the Italian architect Giacomo Quarenghi.[18] In London in 1787, Catherine acquired the collection of sculpture that belonged to Lyde Browne, mostly Ancient Roman marbles. Catherine used them to adorn the Catherine Palace and park in Tsarskoye Selo, but later they became the core of the Classical Antiquities collection of the Hermitage. From 1787 to 1792, Quarenghi designed and built a wing along the Winter Canal with the Raphael Loggias to replicate the loggia in the Apostolic Palace in Rome designed by Donato Bramante and frescoed by Raphael.[14][19][20]

Catherine’s collection of at least 4,000 paintings came to rival the older and more prestigious museums of Western Europe. Catherine took great pride in her collection and actively participated in extensive competitive art gathering and collecting that was prevalent in European royal court culture. Through her art collection she gained European acknowledgment and acceptance and portrayed Russia as an enlightened society. Catherine went on to invest much of her identity in being a patron of the arts. She was particularly fond of the Roman deity Minerva, whose characteristics according to classical tradition are military prowess, wisdom, and patronage of the arts. Using the title Catherine the Minerva, she created new institutions of literature and culture and also participated in many projects of her own, mostly play writing. The representation of Catherine alongside Minerva would come to be a tradition of enlightened patronage in Russia.[21]

Expansion in the 19th century[edit]

In 1815, Alexander I of Russia purchased 38 pictures from the heirs of Joséphine de Beauharnais, most of which had been looted by the French in Kassel during the war. The Hermitage collection of Rembrandts was then considered the largest in the world. Also among Alexander’s purchases from Josephine’s estate were the first four sculptures by the neoclassical Italian sculptor Antonio Canova to enter the Hermitage collection.

Between 1840 and 1843, Vasily Stasov redesigned the interiors of the Southern Pavilion of the Small Hermitage. In 1838, Nicholas I commissioned the neoclassical German architect Leo von Klenze to design a building for the public museum. Space for the museum was made next to the Small Hermitage by the demolition of the Shepelev Palace and royal stables. The construction was overseen by the Russian architects Vasily Stasov and Nikolai Yefimov from 1842 to 1851 and incorporated Quarenghi’s wing with the Raphael Loggias.

The New Hermitage was opened to the public on 5 February 1852.[22] In the same year the Egyptian Collection of the Hermitage Museum emerged and was particularly enriched by items given by the Duke of Leuchtenberg, Nicholas I’s son-in-law. Meanwhile, from 1851 to 1860, the interiors of the Old Hermitage were redesigned by Andrei Stackensneider to accommodate the State Assembly, Cabinet of Ministers and state apartments. Stakenschneider created the Pavilion Hall in the Northern Pavilion of the Small Hermitage from 1851 to 1858.[14]

In 1861, the Hermitage purchased from the Papal government part of the Giampietro Campana collection, which consisted mostly classical antiquities. These included over 500 vases, 200 bronzes and a number of marble statues. The Hermitage acquired Madonna Litta, which was then attributed to Leonardo, in 1865, and Raphael’s Connestabile Madonna in 1870. In 1884 in Paris, Alexander III of Russia acquired the collection of Alexander Basilewski, featuring European medieval and Renaissance artifacts. In 1885, the Arsenal collection of arms and armour, founded by Alexander I of Russia, was transferred from the Catherine Palace in Tsarskoye Selo to the Hermitage. In 1914, Leonardo’s Benois Madonna was added to the collection.

After the October Revolution[edit]

Immediately after the Revolution of 1917, the Imperial Hermitage and the Winter Palace, the former Imperial residence, were proclaimed state museums and eventually merged.

The range of the Hermitage’s exhibits was further expanded when private art collections from several palaces of the Russian Tsars and numerous private mansions were nationalized and redistributed among major Soviet state museums. Particularly notable was the influx of old masters from the Catherine Palace, the Alexander Palace, the Stroganov Palace, and the Yusupov Palace, as well as from other palaces of Saint Petersburg and suburbs.

In 1922, a collection of 19th-century European paintings was transferred to the Hermitage from the Academy of Arts. In turn, in 1927 about 500 important paintings were transferred to the Central Museum of old Western art in Moscow at the insistence of the Soviet authorities.

In 1928, the Soviet government ordered the Hermitage to compile a list of valuable works of art for export. From 1930 to 1934, over two thousand works of art from the Hermitage collection were clandestinely sold at auctions abroad or directly to foreign officials and businesspeople. The sold items included Raphael’s Alba Madonna, Titian’s Venus with a Mirror, and Jan van Eyck’s Annunciation, among other world known masterpieces by Botticelli, Rembrandt, Van Dyck, and others. In 1931 Andrew W. Mellon acquired 21 works of art from the Hermitage and later donated them to form a nucleus of the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C. (see also Soviet sale of Hermitage paintings).

With the German invasion of the Soviet Union in 1941, before the Siege of Leningrad started, two trains with a considerable part of the collections were evacuated to Sverdlovsk. Two bombs and a number of shells hit the museum buildings during the siege. The museum opened an exhibition in November 1944. In October 1945 the evacuated collections were brought back, and in November 1945 the museum reopened.

In 1948, 316 works of Impressionist, post-Impressionist, and modern art from the collection of the Museum of New Western Art in Moscow, originating mostly from the nationalized collections of Sergei Shchukin and Ivan Morozov before the war, were transferred to the Hermitage, including works by Matisse and Picasso.

On 15 June 1985, a man later judged insane attacked Rembrandt’s painting Danaë, displayed in the museum. He threw sulfuric acid on the canvas and cut it twice with a knife. The restoration of the painting had been accomplished by Hermitage conservationists by 1997, and Danaë is now on display behind armoured glass.

The Hermitage since 1991[edit]

In 1991, it became known that some paintings looted by the Red Army in Germany in 1945 were held in the Hermitage. But only in October 1994 did the Hermitage officially announce that it had secretly been holding a major trove of French Impressionist and Post-Impressionist paintings from German private collections. The exhibition «Hidden Treasures Revealed», where 74 of the paintings were displayed for the first time, was opened on 30 March 1995 in the Nicholas Hall of the Winter Palace and lasted a year. Of the paintings, all but one originated from private rather than state German collections, including 56 paintings from the Otto Krebs collection, as well as the collection of Bernhard Koehler and paintings previously belonging to Otto Gerstenberg and his daughter Margarete Scharf, including the world-famous Place de la Concorde by Degas, In the Garden by Renoir, and White House at Night by Van Gogh.[23][24][25] Some of the paintings are now on permanent display in several small rooms in the northeastern corner of the Winter Palace on the first floor.[26][27]

In 1993, the Russian government gave the eastern wing of the nearby General Staff Building across the Palace Square to the Hermitage and the new exhibition rooms in 1999. Since 2003, the Great Courtyard of the Winter Palace has been open to the public.

In 2003, the Hermitage loaned 142 pieces to the University of Michigan Museum of Art for an exhibition titled The Romanovs Collect: European Art from the Hermitage.[28]

In December 2004, the museum discovered another looted work of art: Venus Disarming Mars by Rubens was once in the collection of the Rheinsberg Palace near Berlin, and was apparently looted by Soviet troops from the Königsberg Castle in East Prussia in 1945. At the time, Mikhail Piotrovsky said the painting would be cleaned and displayed.[29]

The museum announced in July 2006 that 221 minor items, including jewelry, Orthodox icons, silverware and richly enameled objects, had been stolen. The value of the stolen items was estimated to be approximately $543,000. By the end of 2006 several of the stolen items had been recovered.[30]

In March 2020, Apple released a continuous 5 hour and 19 minute one shot film recorded entirely on an iPhone 11 Pro detailing many rooms of the museum which highlighted not only the artwork, but also the architecture, and live movement pieces interspersed throughout.[31]

Dependencies[edit]

In recent years, the Hermitage launched several dependencies abroad and domestically.

Hermitage-Kazan Exhibition Center[edit]

The Hermitage dependency in Kazan (Tatarstan, Russia), opened in 2005. It was created with support from President of the Republic of Tatarstan Mintimer Shaimiev and is a subdivision of the Kazan Kremlin State Historical and Architectural Museum-Park. The museum is situated in the Kazan Kremlin in an edifice previously occupied by the Junker School built in the beginning of the 19th century.[32]

Ermitage Italia, Ferrara[edit]

Following the prior experiences in London, Las Vegas, Amsterdam and Kazan, the Hermitage foundation decided to create a further branch in Italy with the launch of a national bid. Several northern Italian cities expressed interest such as Verona, Mantua, Ferrara and Turin. In 2007, the honor was awarded to the city of Ferrara which proposed its Castle Estense as the base. Since then, the new institution called Ermitage Italia started a research and scientific collaboration with the Hermitage foundation.[33]

Hermitage-Vyborg Center[edit]

Hermitage-Vyborg Center was opened in June 2010 in Vyborg, Leningrad Oblast.

Hermitage Exhibition Center, Vladivostok[edit]

A Hermitage branch is due to open in Vladivostok by 2016, and the regional government has allocated more than Rb17.7 million ($558,000) for preliminary reconstruction work on a mansion in Vladivostok’s historic downtown district to house the satellite.[34]

Hermitage-Siberia, Omsk[edit]

The Hermitage-Siberia is due to open in Omsk in 2016.[34]

Guggenheim Hermitage Museum, Vilnius[edit]

In recent years, there have been proposals to open a Vilnius Guggenheim Hermitage Museum in the capital city of Lithuania. Like the former Las Vegas dependency, the museum is to combine artworks from the Saint Petersburg Hermitage with works from the New York Guggenheim Museum.[35]

Former dependencies[edit]

The Guggenheim Hermitage Museum in Las Vegas opened on 7 October 2001 and closed on 11 May 2008.[36] The Hermitage Rooms in London’s Somerset House opened on 25 November 2000.[37] The exhibition was closed permanently in November 2007 due to poor visitor numbers.[38]

The dependency of the Hermitage Museum in Amsterdam was known as the Hermitage Amsterdam, and is located in the former Amstelhof building. It opened on 24 February 2004 in a small building on the Nieuwe Herengracht in Amsterdam, awaiting the closing of the retirement home which still occupied the Amstelhof building until 2007. Between 2007 and 2009, the Amstelhof was renovated and made suitable for the housing of the Amsterdam Hermitage. The Amsterdam Hermitage was opened on 19 June 2009 by President Dmitry Medvedev and Queen Beatrix of the Netherlands.[39] Following Russia’s 2022 invasion of Ukraine, the Amsterdam Hermitage severed ties with St. Petersburg,[40] being renamed to H’Art Museum the following year.[41][42]

Management[edit]

Hermitage directors[edit]

- Florian Gilles

- Stepan Gedeonov (1863–78)

- Alexander Vasilchikov (1879–88)

- Sergei Nikitich Trubetskoi (1888–99)

- Ivan Vsevolozhsky (1899–1909)

- Dmitry Tolstoi (1909–1918)

- Boris Legran (1931–1934)

- Iosif Orbeli (1934–1951)

- Mikhail Artamonov (1951–1964)

- Boris Piotrovsky (1964–1990)

- Mikhail Piotrovsky (1992–present)

Volunteer service[edit]

The Hermitage Volunteer Service offers all those interested a unique opportunity to involve themselves in running this world-renowned museum. The program not only aids the Hermitage with its external and internal activities but also serves as an informal link between the museum staff and the public, bringing the specific knowledge of the museum’s experts to the community. Volunteers may also develop projects reflecting their own personal goals and interests: communicate a feeling of responsibility to the youth so as to help them understand the value of tradition and the necessity of its preservation.

Cats[edit]

A population of cats lives on the museum grounds and serves as an attraction.[43]

In popular culture[edit]

Films[edit]

- Russian Ark (2002), the Russian film by Alexander Sokurov, was filmed entirely in the Hermitage Museum, showing the Winter Palace at various stages of its history.

- War and Peace (1966–67), an Oscar-winning Soviet adaptation of the 1869 novel by Leo Tolstoy, was partially filmed in the Winter Palace.

Television[edit]

Russia-K, a Russian national television channel, has been presenting the various art collections of the Hermitage to the general public for years. There are a series of programs that have aired entitled My Hermitage that have been particularly successful. All of these programs are organized by the Director of the Hermitage, Professor Mikhail Piotrovsky, and are quite similar to the broadcasts created by Academician Boris Piotrovsky, who is Mikhail’s father. These programs were first broadcast through the Soviet Union’s ‘First’ channel, airing at the height of the museum’s boom. During this time, this channel recorded more than three million visitors every year, mostly from the Soviet Union. Another program created by the Hermitage was called The Treasures of St. Petersburg, and was broadcast on the St. Petersburg regional television. This program gave insight into what exhibitions were being displayed at the Hermitage.[44]

Treasures of St Petersburg & The Hermitage, (2003) a three-part documentary series for Channel 5 in the UK, directed by Graham Addicott and produced by Pille Runk.

Hermitage Revealed (2014) is a BBC documentary from Margy Kinmonth. The film tells the story of its journey from imperial palace to state museum, investigating remarkable tales of dedication, devotion, ownership and ultimate sacrifice, showing how the collection came about, how it survived tumultuous revolutionary times and what makes the Hermitage unique today.[45]

Literature[edit]

- To the Hermitage, a 2000 novel by Malcolm Bradbury, retells the story of Diderot’s journey to Russia to meet Catherine the Great in her Hermitage.

- Petersburg, a 1913 novel by Andrey Bely, features the Winter Canal near the palace as one of its central locations, but never names the Winter Palace directly.

- Ghostwritten, by David Mitchell, features as one of its protagonists a woman who works for an art counterfeiting ring whilst masquerading as a docent in a gallery room on the upper floor of the Large Hermitage.

- The Madonnas of Leningrad, a novel by Debra Dean, features the Hermitage during World War II.

- Sancar Seckiner’s 2017 book Thilda’s House (Thilda’nın Evi) includes a chapter highlighting the writer’s experience at the Hermitage Museum by indicating several masterworks of the 15th–19th centuries. ISBN 978-605-4160-88-4

Games[edit]

- The Hermitage appears in the video games Civilization IV, Civilization V and Civilization VI as a wonder of the world.[46]

- The Hermitage appears in the first mission of the Soviet campaign in the video game Command and Conquer: Red Alert 3; it is under attack from forces of the Empire of the Rising Sun.

Gallery[edit]

-

Ancient Egyptian: Limestone stele of a chief potter (18th century BC)

-

Ancient Near East: Urartu deity (7th–5th century BC)

-

-

Ancient Steppes: Pazyryk horseman (3rd century BC)

-

-

-

Indian: statue of Buddha (2nd–3rd century)

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

Flemish Baroque: Self-Portrait by Anthony van Dyck (1622–1623)

-

-

Classicism: Tancred and Herminia by Nicolas Poussin (1649)

-

English: Woman in Blue by Thomas Gainsborough (c. 1770s)

-

Rococo: The Stolen Kiss by Jean-Honoré Fragonard (c. 1780)

-

-

-

Persian: Portrait of Fath Ali Shah (1813–1814)

-

-

-

Post-Impressionism: The Overture to Tannhauser: The Artist’s Mother and Sister by Paul Cézanne (1868)

-

Picasso’s Rose Period: Femme au café (Absinthe Drinker) by Pablo Picasso (1901–02)

-

-

-

Maratha India: A Maratha Armor and Helmet

-

Abstract: Composition VI by Wassily Kandinsky (1913)

See also[edit]

- List of most visited art museums

- List of museums in Saint Petersburg

- Baldin Collection

Notes[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ «Hermitage in Figures and Facts». Hermitagemuseum.org. Retrieved 30 June 2020.

- ^ The Art Newspaper annual survey, March 28, 2023.

- ^ «Page 7» (PDF). Retrieved 6 May 2022.

- ^ «The Art Newspaper», March 2023

- ^ «Page 20» (PDF). Retrieved 6 May 2022.

- ^ «Mikhail Piotrovsky». The State Hermitage Museum. Retrieved 19 June 2016.

- ^ «Государственный Эрмитаж» [The State hermitage Museum] (in Russian). Culture.ru. Retrieved 9 February 2020.

- ^ «Traditional Meeting with Journalists: Farewell to White Nights — 2005». www.hermitagemuseum.org. Archived from the original on 17 February 2012.

- ^ «The Room of French Painting of the Second Half of the 19th Century (Daumier, Manet, Degas)». Hermitage Museum.

- ^ «Claude Monet Room».

- ^ Norman 1997, pp. 28–29

- ^ Frank 2002

- ^ a b «Hermitage History,» www.hermitagemuseum.org.[full citation needed]

- ^ a b c Saint Petersburg Encyclopedia — Hermitage Buildings (entry) Archived 24 February 2012 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Piotrovsky, Mikhail, «The Hermitage in the Context of the City,» Museum International 55, no. 1, 79–80.

- ^ Mason, Mary Willan, «The Treasures of Catherine the Great from the State Hermitage Museum St. Petersburg,» Antiques & Collecting Magazine 106, no. 3, 62.

- ^ Norman 1997, p. 23

- ^ Norman 1997, pp. 37–38

- ^ «Hermitage History: The Raphael Loggias». www.hermitagemuseum.org. Archived from the original on 11 September 2012. Retrieved 7 September 2012.

- ^ «Hermitage History: Timeline: 1771–1787: Construction of the Great Hermitage». www.hermitagemuseum.org. Archived from the original on 28 June 2012. Retrieved 7 September 2012.

- ^ Dianina, Katia, «Art and Authority: The Hermitage of Catherine the Great,» Russian Review 63, no. 4, 634–636.

- ^ Norman 1997, p. 1

- ^ John Russell (4 October 1994). «Hermitage Reveals It Hid Trove of Impressionist Art». The New York Times. Retrieved 25 February 2014.

- ^ Steven Erlanger (30 March 1995). «Restitution Hermitage, in Its Manner, Displays Its Looted Art». The New York Times.

- ^ «Hermitage History: Timeline: 1995: The exhibition Hidden Treasures Revealed». www.hermitagemuseum.org. Archived from the original on 3 March 2014.

- ^ «Virtual Tour: 70: Room Displaying «Unknown Masterpieces»«. www.hermitagemuseum.org. Archived from the original on 9 February 2014.

- ^ «Virtual Tour: 71: Room Displaying «Unknown Masterpieces»«. www.hermitagemuseum.org. Archived from the original on 5 October 2013.

- ^ «News | Museum of Art (UMMA) | U-M». umma.umich.edu. Retrieved 25 September 2020.

- ^ John Varoli (20 December 2004). «St Petersburg: Rubens looted from Germany discovered at Hermitage». The Art Newspaper. Codart.nl. Retrieved 29 November 2012.

- ^ Galina Stolyarova (1 August 2006). «Stolen Russian Museum Items Not Insured». The Washington Post. Retrieved 29 November 2012.

- ^ Archived at Ghostarchive and the Wayback Machine: «A one-take journey through Russia’s iconic Hermitage museum | Shot on iPhone 11 Pro». YouTube.

- ^ «The Hermitage-Kazan Exhibition Center, Tatarstan». www.hermitagemuseum.org. Archived from the original on 8 August 2014.

- ^ «ErmitageItalia Homepage». Ermitageitalia.com. Archived from the original on 16 March 2012. Retrieved 7 September 2012.

- ^ a b Sophia Kishkovsky (6 November 2013), Launch (museum) satellites, says Putin Archived 7 November 2013 at the Wayback Machine The Art Newspaper.

- ^ Ben Sisario (12 June 2008). «ARTS, BRIEFLY; Lithuania Approves Guggenheim Project». The New York Times. Retrieved 30 May 2012.

- ^ «Guggenheim Hermitage Museum in Las Vegas concludes seven-year residency at the Venetian Hotel-Resort-Casino» (Press release). Guggenheim Foundation. 9 April 2008. Archived from the original on 4 January 2013. Retrieved 29 November 2012.

- ^ «The Hermitage Rooms in Somerset House, London». www.hermitagemuseum.org. Archived from the original on 8 August 2014.

- ^ Philippa Stockley (30 October 2007). «Josephine’s farewell from the Hermitage». The Evening Standard. standard.co.uk. Retrieved 29 November 2012.

- ^ Reuters.com — Russia’s Hermitage museum opens Amsterdam branch

- ^ Solomon, Tessa (4 March 2022). «Amsterdam’s Hermitage Museum Outpost Severs Ties with St. Petersburg Flagship Institution». ARTnews. Archived from the original on 5 September 2023. Retrieved 5 September 2023.

- ^ «Hermitage to become H’ART Museum». H’ART Museum. 1 September 2023. Archived from the original on 5 September 2023. Retrieved 5 September 2023.

- ^ «Amsterdam’s Hermitage museum is renamed after cutting ties with Russia following Ukraine invasion». Associated Press News. 26 June 2023. Archived from the original on 5 September 2023. Retrieved 5 September 2023.

- ^ Cole, Teresa Levonian (5 February 2016). «St Petersburg: the cats of the Hermitage». The Telegraph. ISSN 0307-1235. Retrieved 6 March 2018.

- ^ Matveev, Vladimir, «The Hermitage and its Links with Regions of Russia,» Museum International 55, no. 1, 68.

- ^ «Hermitage Revealed». IMDb.

- ^ «Civilization Fanatics’ Forums — View Single Post — Civ5 Confirmed Features and Versions». Forums.civfanatics.com. Retrieved 7 September 2012.

Sources[edit]

| External video |

|---|

- Frank, Christoph (2002), «Die Gemäldesammlungen Gotzkowsky, Eimbke und Stein: Zur Berliner Sammlungsgeschichte während des Siebenjährigen Krieges.», in Michael North (ed.), Kunstsammeln und Geschmack im 18. Jahrhundert (in German), Berlin: Berlin Verlag Spitz, pp. 117–194, ISBN 3-8305-0312-1

- Norman, Geraldine (1997), The Hermitage; The Biography of a Great Museum, New York: Fromm International, ISBN 0-88064-190-8

Further reading[edit]

- Dutch and Flemish paintings from the Hermitage . New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art. 1988.

External links[edit]

59°56′26″N 30°18′49″E / 59.94056°N 30.31361°E

РПЦ и реституция ,

0

Глава Эрмитажа — об уходах директоров музеев и передаче ценностей церкви

Интервью главы Эрмитажа Михаила Пиотровского об увольнениях директоров музеев в России

Video

Любого директора любого музея в России «могут уволить без всяких разговоров и без всяких прав на защиту», рассказал в интервью телеканалу РБК директор Эрмитажа Михаил Пиотровский. По его словам, это связано с тем, что у каждого директора свои сроки контрактов, и «ничего экстраординарного не произошло». Одна из ключевых проблем в российской культуре — что «нужно воспитать срочно молодых людей, которые должны все взять в свои руки и справиться с той ситуацией, которая сейчас существует».

Об этом, отменяют ли культуру в разных странах и возвращении музейных ценностей церкви — в полном видеоинтервью.