|

Government of Japan 日本国政府 |

|

|---|---|

Seal of the Government |

|

| Polity type | Unitary parliamentary constitutional monarchy |

| Constitution | Constitution of Japan |

| Formation | 1885; 138 years ago |

| Legislative branch | |

| Name | National Diet |

| Meeting place | National Diet Building |

| Upper house | |

| Name | House of Councillors |

| Lower house | |

| Name | House of Representatives |

| Executive branch | |

| Head of State | |

| Title | Emperor |

| Currently | Naruhito |

| Head of Government | |

| Title | Prime Minister |

| Currently | Fumio Kishida |

| Appointer | Emperor |

| Cabinet | |

| Name | Cabinet of Japan |

| Leader | Prime Minister |

| Appointer | Prime Minister |

| Headquarters | Prime Minister’s Official Residence |

| Judicial branch | |

| The Supreme Court of Japan | |

| Seat | Chiyoda |

| Government of Japan | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Japanese name | |||

| Kanji | 日本国政府 | ||

| Hiragana | にほんこくせいふ (formal) にっぽんこくせいふ (informal) |

||

|

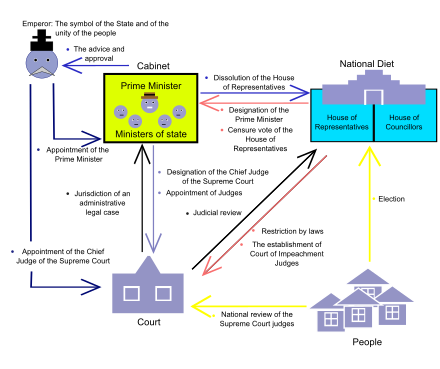

The Government of Japan consists of legislative, executive and judiciary branches and is based on popular sovereignty. The Government runs under the framework established by the Constitution of Japan, adopted in 1947. It is a unitary state, containing forty-seven administrative divisions, with the Emperor as its Head of State.[1] His role is ceremonial and he has no powers related to Government.[2] Instead, it is the Cabinet, comprising the Ministers of State and the Prime Minister, that directs and controls the Government and the civil service. The Cabinet has the executive power and is formed by the Prime Minister, who is the Head of Government.[3][4] The Prime Minister is nominated by the National Diet and appointed to office by the Emperor.[5][6]

The National Diet is the legislature, the organ of the Legislative branch. It is bicameral, consisting of two houses with the House of Councilors being the upper house, and the House of Representatives being the lower house. Its members are directly elected by the people, who are the source of sovereignty.[7] It is defined as the supreme organ of sovereignty in the Constitution. The Supreme Court and other lower courts make up the Judicial branch and have all the judicial powers in the state. It has ultimate judicial authority to interpret the Japanese constitution and the power of judicial review. They are independent from the executive and the legislative branches.[8] Judges are nominated or appointed by the Cabinet and never removed by the executive or the legislature except during impeachment.

History[edit]

Before The Meiji Restoration, Japan was ruled by the government of a successive military shōgun. During this period, effective power of the government resided in the Shōgun, who officially ruled the country in the name of the Emperor.[9] The Shōgun were the hereditary military governors, with their modern rank equivalent to a generalissimo. Although the Emperor was the sovereign who appointed the Shōgun, his roles were ceremonial and he took no part in governing the country.[10] This is often compared to the present role of the Emperor, whose official role is to appoint the Prime Minister.[11]

«Taiseihokan»(大政奉還)The return of political power to the Emperor (to the Imperial Court) in 1868 meanet the resignation of Shōgun Tokugawa Yoshinobu, agreeing to «be the instrument for carrying out» the Emperor’s orders.[12] This event restored the country to Imperial rule and the proclamation of the Empire of Japan. In 1889, the Meiji Constitution was adopted in a move to strengthen Japan to the level of western nations, resulting in the first parliamentary system in Asia.[13] It provided a form of mixed constitutional-absolute monarchy, with an independent judiciary, based on the Prussian model of the time.[14]

A new aristocracy known as the kazoku was established. It merged the ancient court nobility of the Heian period, the kuge, and the former daimyō, feudal lords subordinate to the shōgun.[15] It also established the Imperial Diet, consisting of the House of Representatives and the House of Peers. Members of the House of Peers were made up of the Imperial Family, the Kazoku, and those nominated by the Emperor,[16] while members of the House of Representatives were elected by direct male suffrage.[17] Despite clear distinctions between powers of the executive branch and the Emperor in the Meiji Constitution, ambiguity and contradictions in the Constitution eventually led to a political crisis.[18] It also devalued the notion of civilian control over the military, which meant that the military could develop and exercise a great influence on politics.[19]

Following the end of World War II, the present Constitution of Japan was adopted. It replaced the previous Imperial rule with a form of Western-style liberal democracy.[20]

As of 2020, the Japan Research Institute found the national government is mostly analog, because only 7.5% (4,000 of the 55,000) administrative procedures can be completed entirely online. The rate is 7.8% at the Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry, 8% at the Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications, and only 1.3% at the Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries.[21]

On 12 February, 2021, Tetsushi Sakamoto was appointed as the Minister of Loneliness to alleviate social isolation and loneliness across different age groups and genders.[22]

The Emperor[edit]

The Emperor of Japan (天皇) is the head of the Imperial Family and the ceremonial head of state. He is defined by the Constitution to be «the symbol of the State and of the unity of the people».[7] However, his role is entirely ceremonial and representative in nature. As explicitly stated in article 4 of the Constitution, he has no powers related to government.[23]

Article 6 of the Constitution of Japan delegates the Emperor the following ceremonial roles:

- Appointment of the Prime Minister as designated by the Diet.

- Appointment of the Chief Justice of the Supreme Court as designated by the Cabinet.

While the Cabinet is the source of executive power and most of its power is exercised directly by the Prime Minister, several of its powers are exercised through the Emperor. The powers exercised via the Emperor, as stipulated by Article 7 of the Constitution, are:

- Promulgation of amendments of the constitution, laws, cabinet orders and treaties.

- Dissolution of the House of Representatives.

- Proclamation of general election of members of the Diet.

- Attestation of the appointment and dismissal of Ministers of State and other officials as provided for by law, and of full powers and credentials of Ambassadors and Ministers.

- Attestation of general and special amnesty, commutation of punishment, reprieve, and restoration of rights.

- Awarding of honors.

- Attestation of instruments of ratification and other diplomatic documents as provided for by law.

- Receiving foreign ambassadors and ministers.

- Performance of ceremonial functions.

These powers are exercised in accordance with the binding advice of the Cabinet.

The Emperor is known to hold the nominal ceremonial authority. For example, he is the only person that has the authority to appoint the Prime Minister, even though the Diet has the power to designate the person fitted for the position. One such example can be prominently seen in the 2009 Dissolution of the House of Representatives. The House was expected to be dissolved on the advice of the Prime Minister, but was temporarily unable to do so for the next general election, as both the Emperor and Empress were visiting Canada.[24][25]

In this manner, the Emperor’s modern role is often compared to those of the Shogunate period and much of Japan’s history, whereby the Emperor held great symbolic authority but had little political power; which is often held by others nominally appointed by the Emperor himself. Today, a legacy has somewhat continued for a retired Prime Minister who still wields considerable power, to be called a Shadow Shogun (闇将軍).[26]

Unlike his European counterparts, the Emperor is not the source of sovereign power and the government does not act under his name. Instead, the Emperor represents the State and appoints other high officials in the name of the State, in which the Japanese people hold sovereignty.[27] Article 5 of the Constitution, in accordance with the Imperial Household Law, allows a regency to be established in the Emperor’s name, should the Emperor be unable to perform his duties.[28]

On November 20, 1989, the Supreme Court ruled it doesn’t have judicial power over the Emperor.[29]

The Imperial House of Japan is said to be the oldest continuing hereditary monarchy in the world.[30] According to the Kojiki and Nihon Shoki, Japan was founded by the Imperial House in 660 BC by Emperor Jimmu (神武天皇).[31] Emperor Jimmu was the first Emperor of Japan and the ancestor of all of the Emperors that followed.[32] He is, according to Japanese mythology, the direct descendant of Amaterasu (天照大御神), the sun goddess of the native Shinto religion, through Ninigi, his great-grandfather.[33][34]

The Current Emperor of Japan (今上天皇) is Naruhito. He was officially enthroned on May 1, 2019, following the abdication of his father.[35][36] He is styled as His Imperial Majesty (天皇陛下), and his reign bears the era name of Reiwa (令和). Fumihito is the heir presumptive to the Chrysanthemum Throne.

Executive[edit]

The Executive branch of Japan is headed by the Prime Minister. The Prime Minister is the head of the Cabinet, and is designated by the legislative organ, the National Diet.[5] The Cabinet consists of the Ministers of State and may be appointed or dismissed by the Prime Minister at any time.[4] Explicitly defined to be the source of executive power, it is in practice, however, mainly exercised by the Prime Minister. The practice of its powers is responsible to the Diet, and as a whole, should the Cabinet lose confidence and support to be in office by the Diet, the Diet may dismiss the Cabinet en masse with a motion of no confidence.[37]

Prime Minister[edit]

The Prime Minister of Japan (内閣総理大臣) is designated by the National Diet and serves a term of four years or less; with no limits imposed on the number of terms the Prime Minister may hold. The Prime Minister heads the Cabinet and exercises «control and supervision» of the executive branch, and is the head of government and commander-in-chief of the Japan Self-Defense Forces.[38] The prime minister is vested with the power to present bills to the Diet, to sign laws, to declare a state of emergency, and may also dissolve the Diet’s House of Representatives at will.[39] The prime minister presides over the Cabinet and appoints, or dismisses, the other Cabinet ministers.[4]

Both houses of the National Diet designates the Prime Minister with a ballot cast under the run-off system. Under the Constitution, should both houses not agree on a common candidate, then a joint committee is allowed to be established to agree on the matter; specifically within a period of ten days, exclusive of the period of recess.[40] However, if both houses still do not agree to each other, the decision made by the House of Representatives is deemed to be that of the National Diet.[40] Upon designation, the Prime Minister is presented with their commission, and then formally appointed to office by the Emperor.[6]

As a candidate designated by the Diet, the prime minister is required to report to the Diet whenever demanded.[41] The prime minister must also be both a civilian and a member of either house of the Diet.[42]

| No. | Name (English) | Name (Japanese) | Gender | Took office | Left office | Term | Cabinets |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Junichiro Koizumi | 小泉 純一郎 | Male | April 26, 2001 | September 26, 2006 | 5 years, 153 days | 87th: Koizumi I (R1) (R2) 88th: Koizumi II (R) 89th: Koizumi III (R) |

| 2 | Shinzo Abe | 安倍 晋三 | Male | September 26, 2006 | September 26, 2007 | 1 year, 0 days | 90th: S. Abe I (R) |

| 3 | Yasuo Fukuda | 福田 康夫 | Male | September 26, 2007 | September 24, 2008 | 364 days | 91st: Y. Fukuda (R) |

| 4 | Tarō Asō | 麻生 太郎 | Male | September 24, 2008 | September 16, 2009 | 357 days | 92nd: Asō |

| 5 | Yukio Hatoyama | 鳩山 由紀夫 | Male | September 16, 2009 | June 8, 2010 | 265 days | 93rd: Y. Hatoyama |

| 6 | Naoto Kan | 菅 直人 | Male | June 8, 2010 | September 2, 2011 | 1 year, 86 days | 94th: Kan (R1) (R2) |

| 7 | Yoshihiko Noda | 野田 佳彦 | Male | September 2, 2011 | December 26, 2012 | 1 year, 115 days | 95th: Noda (R1) (R2) (R3) |

| 8 | Shinzo Abe | 安倍 晋三 | Male | December 26, 2012 | September 16, 2020 | 7 years, 265 days | 96th: S. Abe II (R) 97th: S. Abe III (R1) (R2) (R3) 98th: S. Abe IV (R1) (R2) |

| 9 | Yoshihide Suga | 菅 義偉 | Male | September 16, 2020 | October 4, 2021 | 1 year, 18 days | 99th: Suga |

| 10 | Fumio Kishida | 岸田 文雄 | Male | October 4, 2021 | Present | 1 year, 354 days | 100th: Kishida I 101st: Kishida II |

The Cabinet[edit]

The Cabinet of Japan (内閣) consists of the Ministers of State and the Prime Minister. The members of the Cabinet are appointed by the Prime Minister, and under the Cabinet Law, the number of members of the Cabinet appointed, excluding the Prime Minister, must be fourteen or less, but may only be increased to nineteen should a special need arise.[43][44] Article 68 of the Constitution states that all members of the Cabinet must be civilians and the majority of them must be chosen from among the members of either house of the National Diet.[45] The precise wording leaves an opportunity for the Prime Minister to appoint some non-elected Diet officials.[46] The Cabinet is required to resign en masse while still continuing its functions, till the appointment of a new Prime Minister, when the following situation arises:

- The Diet’s House of Representatives passes a non-confidence resolution, or rejects a confidence resolution, unless the House of Representatives is dissolved within the next ten days.

- When there is a vacancy in the post of the Prime Minister, or upon the first convocation of the Diet after a general election of the members of the House of Representatives.

Conceptually deriving legitimacy from the Diet, whom it is responsible to, the Cabinet exercises its power in two different ways. In practice, much of its power is exercised by the Prime Minister, while others are exercised nominally by the Emperor.[3]

Article 73 of the Constitution of Japan expects the Cabinet to perform the following functions, in addition to general administration:

- Administer the law faithfully; conduct affairs of state.

- Manage foreign affairs.

- Conclude treaties. However, it shall obtain prior or, depending on circumstances, subsequent approval of the Diet.

- Administer the civil service, in accordance with standards established by law.

- Prepare the budget, and present it to the Diet.

- Enact cabinet orders in order to execute the provisions of this Constitution and of the law. However, it cannot include penal provisions in such cabinet orders unless authorized by such law.

- Decide on general amnesty, special amnesty, commutation of punishment, reprieve, and restoration of rights.

Under the Constitution, all laws and cabinet orders must be signed by the competent Minister and countersigned by the Prime Minister, before being formally promulgated by the Emperor. Also, all members of the Cabinet cannot be subject to legal action without the consent of the Prime Minister; however, without impairing the right to take legal action.[47]

As of 13 September 2023, the makeup of the Cabinet:[48]

101st Cabinet of Japan Second Kishida Cabinet (Second Reshuffle) |

|||||

| Color key: Liberal Democratic Komeito MR: member of the House of Representatives, MC: member of the House of Councillors, B: bureaucrat |

|||||

| Minister Constituency |

Office(s) | Department | Took Office | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cabinet ministers | |||||

|

Fumio Kishida MR for Hiroshima 1st |

Prime Minister | Cabinet Office | 4 October 2021 (23 months ago) |

|

|

Junji Suzuki MR for Aichi 7th |

Minister for Internal Affairs and Communications | Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications | 13 September 2023 (10 days ago) |

|

|

Ryuji Koizumi MR for Saitama 11th |

Minister of Justice | Ministry of Justice | 13 September 2023 (10 days ago) |

|

|

Yōko Kamikawa MR for Shizuoka 1st |

Minister for Foreign Affairs | Ministry of Foreign Affairs | 13 September 2023 (10 days ago) |

|

|

Shun’ichi Suzuki MR for Iwate 2nd |

Minister of Finance Minister of State for Financial Services Minister in charge of Overcoming Deflation |

Ministry of Finance Financial Services Agency |

4 October 2021 (23 months ago) |

|

|

Masahito Moriyama MR for Kinki PR block |

Minister of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology Minister in charge of Education Rebuilding |

Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology | 13 September 2023 (10 days ago) |

|

|

Keizō Takemi MC for Tokyo at-large |

Minister of Health, Labour and Welfare | Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare | 13 September 2023 (10 days ago) |

|

|

Ichiro Miyashita MR for Nagano 5th |

Minister of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries | Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries | 13 September 2023 (10 days ago) |

|

|

Yasutoshi Nishimura MR for Hyōgo 9th |

Minister of Economy, Trade and Industry Minister in charge of Industrial Competitiveness Minister for Economic Cooperation with Russia Minister in charge of the Response to the Economic Impact caused by the Nuclear Accident Minister of State for the Nuclear Damage Compensation and Decommissioning Facilitation Corporation |

Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry | 10 August 2022 (13 months ago) |

|

|

Tetsuo Saito MR for Hiroshima 3rd |

Minister of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism Minister in charge of Water Cycle Policy Minister for the World Horticultural Exhibition Yokohama 2027 |

Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism | 4 October 2021 (23 months ago) |

|

|

Shintaro Ito MR for Miyagi 4th |

Minister of the Environment Minister of State for Nuclear Emergency Preparedness |

Ministry of the Environment | 13 September 2023 (10 days ago) |

|

|

Minoru Kihara MR for Kumamoto 1st |

Minister of Defense | Ministry of Defense | 13 September 2023 (10 days ago) |

|

|

Hirokazu Matsuno MR for Chiba 3rd |

Chief Cabinet Secretary Minister in charge of Mitigating the Impact of U.S. Forces in Okinawa Minister in charge of the Abductions Issue Minister in Charge of Promoting Vaccinations |

Cabinet Secretariat | 4 October 2021 (23 months ago) |

|

|

Taro Kono MR for Kanagawa 15th |

Minister for Digital Transformation Minister of State for Digital Reform Minister in charge of Administrative Reform Minister of State for Consumer Affairs and Food Safety Minister in charge of Civil Service Reform |

Digital Agency Cabinet Office |

10 August 2022 (13 months ago) |

|

|

Shinako Tsuchiya MR for Saitama 13th |

Minister of Reconstruction Minister in charge of Comprehensive Policy Coordination for Revival from the Nuclear Accident at Fukushima |

Reconstruction Agency | 13 September 2023 (10 days ago) |

|

|

Yoshifumi Matsumura MC for Kumamoto at-large |

Chairperson of the National Public Safety Commission Minister in charge of Building National Resilience Minister in charge of Territorial Issues Minister in charge of Civil Service Reform Minister of State for Disaster Management and Ocean Policy |

National Public Safety Commission Cabinet Office |

13 September 2023 (10 days ago) |

|

|

Ayuko Kato MR for Yamagata 3rd |

Minister in charge of Policies Related to Children Minister in charge of Cohesive Society Minister in charge of Women’s Empowerment Minister in charge of Measures for Loneliness and Isolation Minister of State for Measures for Declining Birthrate Minister of State for Gender Equality |

Children and Families Agency Cabinet Office |

13 September 2023 (10 days ago) |

|

|

Yoshitaka Shindō MR for Saitama 2nd |

Minister in charge of Economic Revitalization Minister in charge of New Capitalism Minister in charge of Startups Minister in charge of Measures for Novel Coronavirus Disease and Health Crisis Management Minister in charge of Social Security Reform Minister of State for Economic and Fiscal Policy |

Cabinet Office | 13 September 2023 (10 days ago) |

|

|

Sanae Takaichi MR for Nara 2nd |

Minister in charge of Economic Security Minister of State for «Cool Japan» Strategy Minister of State for Intellectual Property Strategy Minister of State for Science and Technology Policy Minister of State for Space Policy Minister of State for Economic Security |

Cabinet Office | 10 August 2022 (13 months ago) |

|

|

Hanako Jimi MC for National PR block |

Minister of State for Okinawa and Northern Territories Affairs Minister of State for Regional Revitalization Minister of State for Regulatory Reform Minister of State for Ainu-Related Policies Minister in charge of Digital Garden City Nation Vision Minister for the World Expo 2025 |

Cabinet Office | 13 September 2023 (10 days ago) |

Ministries and agencies[edit]

The ministries of Japan (中央省庁, Chuo shōcho) consist of eleven executive ministries and the Cabinet Office. Each ministry is headed by a Minister of State, which are mainly senior legislators, and are appointed from among the members of the Cabinet by the Prime Minister. The Cabinet Office, formally headed by the Prime Minister, is an agency that handles the day-to-day affairs of the Cabinet. The ministries are the most influential part of the daily-exercised executive power, and since few ministers serve for more than a year or so necessary to grab hold of the organisation, most of its power lies within the senior bureaucrats.[49]

Below is a series of ministry-affiliated government agencies and bureaus responsible for government procedures and activities as of 23 August 2022.[50]

- Cabinet Office

- National Public Safety Commission

- National Police Agency

- Consumer Affairs Agency

- Financial Services Agency

- Fair Trade Commission

- Food Safety Commission

- Personal Information Protection Commission

- Imperial Household Agency

- Gender Equality Bureau

- Council on Economic and Fiscal Policy

- Atomic Energy Commission

- International Peace Cooperation

- Council for Science, Technology and Innovation

- Headquarters for Ocean Policy

- Northern Territories Affairs Administration

- Public Relations Office of the Government of Japan

- Cabinet Secretariat

- National Information Security Centre

- National Personnel Authority

- Coordination Office of Measures on Emerging Infectious Diseases

- Headquarters for the Abduction Issue

- Cabinet Legislation Bureau

- Office of Policy Planning and Coordination on Territory and Sovereignty

- Reconstruction Agency

- Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications

- Environmental Dispute Coordination Commission

- Fire and Disaster Management Agency

- Ministry of Justice

- Public Security Examination Commission

- Public Security Intelligence Agency

- Public Prosecutors Office

- Immigration Services Agency

- Ministry of Foreign Affairs

- Ministry of Finance

- National Tax Agency

- Japan Customs

- Ministry of Defense

- Acquisition, Technology and Logistics Agency

- Japan Self-Defence Forces (Ground / Maritime / Air)

- Joint Staff

- Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (MEXT)

- Education Policy Bureau

- Elementary and Secondary Education Bureau

- Higher Education Bureau

- Science and Technology Policy Bureau

- Research Promotion Bureau

- Agency for Cultural Affairs

- Japan Sports Agency

- The Japan Art Academy

- National Institute for Educational Policy Research

- National Institute of Science and Technology Policy

- The Japan Academy

- Headquarters for Earthquake Research Promotion

- Japanese National Commission for UNESCO

- Ministry of Health, Labour, and Welfare

- Pension Service

- Central Labour Relations Commission

- Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries

- Fisheries Agency

- Forestry Agency

- Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry (METI)

- Agency for Natural Resources and Energy

- Small and Medium Enterprise Agency

- Japan Patent Office

- Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism (MLIT)

- Japan Transport Safety Board

- Japan Tourism Agency

- Japan Meteorological Agency

- Japan Coast Guard

- Ministry of the Environment

- Nuclear Regulation Authority

- Board of Audit

Legislative[edit]

The Legislative branch organ of Japan is the National Diet (国会). It is a bicameral legislature, composing of a lower house, the House of Representatives, and an upper house, the House of Councillors. Empowered by the Constitution to be «the highest organ of State power» and the only «sole law-making organ of the State», its houses are both directly elected under a parallel voting system and is ensured by the Constitution to have no discrimination on the qualifications of each members; whether be it based on «race, creed, sex, social status, family origin, education, property or income». The National Diet, therefore, reflects the sovereignty of the people; a principle of popular sovereignty whereby the supreme power lies within, in this case, the Japanese people.[7][51]

The Diet responsibilities includes the making of laws, the approval of the annual national budget, the approval of the conclusion of treaties and the selection of the Prime Minister. In addition, it has the power to initiate draft constitutional amendments, which, if approved, are to be presented to the people for ratification in a referendum before being promulgated by the Emperor, in the name of the people.[52] The Constitution also enables both houses to conduct investigations in relation to government, demand the presence and testimony of witnesses, and the production of records, as well as allowing either house of the Diet to demand the presence of the Prime Minister or the other Minister of State, in order to give answers or explanations whenever so required.[41] The Diet is also able to impeach Court judges convicted of criminal or irregular conduct. The Constitution, however, does not specify the voting methods, the number of members of each house, and all other matters pertaining to the method of election of the each members, and are thus, allowed to be determined for by law.[53]

Under the provisions of the Constitution and by law, all adults aged over 18 are eligible to vote, with a secret ballot and a universal suffrage, and those elected have certain protections from apprehension while the Diet is in session.[54] Speeches, debates, and votes cast in the Diet also enjoy parliamentary privileges. Each house is responsible for disciplining its own members, and all deliberations are public unless two-thirds or more of those members present passes a resolution agreeing it otherwise. The Diet also requires the presence of at least one-third of the membership of either house in order to constitute a quorum.[55] All decisions are decided by a majority of those present, unless otherwise stated by the Constitution, and in the case of a tie, the presiding officer has the right to decide the issue. A member cannot be expelled, however, unless a majority of two-thirds or more of those members present passes a resolution therefor.[56]

Under the Constitution, at least one session of the Diet must be convened each year. The Cabinet can also, at will, convoke extraordinary sessions of the Diet and is required to, when a quarter or more of the total members of either house demands it.[57] During an election, only the House of Representatives is dissolved. The House of Councillors is however, not dissolved but only closed, and may, in times of national emergency, be convoked for an emergency session.[58] The Emperor both convokes the Diet and dissolves the House of Representatives, but only does so on the advice of the Cabinet.

For bills to become Law, they are to be first passed by both houses of the National Diet, signed by the Ministers of State, countersigned by the Prime Minister, and then finally promulgated by the Emperor; however, without specifically giving the Emperor the power to oppose legislation.

House of Representatives[edit]

The House of Representatives of Japan (衆議院) is the Lower house, with the members of the house being elected once every four years, or when dissolved, for a four-year term.[59] As of November 18, 2017, it has 465 members. Of these, 176 members are elected from 11 multi-member constituencies by a party-list system of proportional representation, and 289 are elected from single-member constituencies. 233 seats are required for majority. The House of Representatives is the more powerful house out of the two, it is able to override vetoes on bills imposed by the House of Councillors with a two-thirds majority. It can, however, be dissolved by the Prime Minister at will.[39] Members of the house must be of Japanese nationality; those aged 18 years and older may vote, while those aged 25 years and older may run for office in the lower house.[54]

The legislative powers of the House of Representatives is considered to be more powerful than that of the House of Councillors. While the House of Councillors has the ability to veto most decisions made by the House of Representatives, some however, can only be delayed. This includes the legislation of treaties, the budget, and the selection of the Prime Minister. The Prime Minister, and collectively his Cabinet, can in turn, however, dissolve the House of Representatives whenever intended.[39] While the House of Representatives is considered to be officially dissolved upon the preparation of the document, the House is only formally dissolved by the dissolution ceremony.[60] The dissolution ceremony of the House is as follows:[61]

- The document is rubber stamped by the Emperor, and wrapped in a purple silk cloth; an indication of a document of state act, done on behalf of the people.

- The document is passed on to the Chief Cabinet Secretary at the House of Representatives President’s reception room.

- The document is taken to the Chamber for preparation by the General-Secretary.

- The General-Secretary prepares the document for reading by the Speaker.

- The Speaker of the House of Representatives promptly declares the dissolution of the House.

- The House of Representatives is formally dissolved.

It is customary that, upon the dissolution of the House, members will shout the Three Cheers of Banzai (萬歲).[60][62]

House of Councillors[edit]

The House of Councillors of Japan (参議院) is the Upper house, with half the members of the house being elected once every three years, for a six-year term. As of November 18, 2017, it has 242 members. Of these, 73 are elected from the 47 prefectural districts, by single non-transferable votes, and 48 are elected from a nationwide list by proportional representation with open lists. The House of Councillors cannot be dissolved by the Prime Minister.[58] Members of the house must be of Japanese nationality; those aged 18 years and older may vote, while those aged 30 years and older may run for office in the upper house.[54]

As the House of Councillors can veto a decision made by the House of Representatives, the House of Councillors can cause the House of Representatives to reconsider its decision. The House of Representatives however, can still insist on its decision by overriding the veto by the House of Councillors with a two-thirds majority of its members present. Each year, and when required, the National Diet is convoked at the House of Councillors, on the advice of the Cabinet, for an extra or an ordinary session, by the Emperor. A short speech is, however, usually first made by the Speaker of the House of Representatives before the Emperor proceeds to convoke the Diet with his Speech from the throne.[63]

Judicial[edit]

The Judicial branch of Japan consists of the Supreme Court, and four other lower courts; the High Courts, District Courts, Family Courts and Summary Courts.[64] Divided into four basic tiers, the Court’s independence from the executive and legislative branches are guaranteed by the Constitution, and is stated as: «no extraordinary tribunal shall be established, nor shall any organ or agency of the Executive be given final judicial power»; a feature known as the Separation of Powers.[8] Article 76 of the Constitution states that all the Court judges are independent in the exercise of their own conscience and that they are only bounded by the Constitution and the laws.[65] Court judges are removable only by public impeachment, and can only be removed, without impeachment, when they are judicially declared mentally or physically incompetent to perform their duties.[66] The Constitution also explicitly denies any power for executive organs or agencies to administer disciplinary actions against judges.[66] However, a Supreme Court judge may be dismissed by a majority in a referendum; of which, must occur during the first general election of the National Diet’s House of Representatives following the judge’s appointment, and also the first general election for every ten years lapse thereafter.[67] Trials must be conducted, with judgment declared, publicly, unless the Court «unanimously determines publicity to be dangerous to public order or morals»; with the exception for trials of political offenses, offenses involving the press, and cases wherein the rights of people as guaranteed by the Constitution, which cannot be deemed and conducted privately.[68] Court judges are appointed by the Cabinet, in attestation of the Emperor, while the Chief Justice is appointed by the Emperor, after being nominated by the Cabinet; which in practice, known to be under the recommendation of the former Chief Justice.[69]

The Legal system in Japan has been historically influenced by Chinese law; developing independently during the Edo period through texts such as Kujikata Osadamegaki.[70] It has, however, changed during the Meiji Restoration, and is now largely based on the European civil law; notably, the civil code based on the German model still remains in effect.[71] A quasi-jury system has recently came into use, and the legal system also includes a bill of rights since May 3, 1947.[72] The collection of Six Codes makes up the main body of the Japanese statutory law.[71]

All Statutory Laws in Japan are required to be rubber stamped by the Emperor with the Privy Seal of Japan (天皇御璽), and no Law can take effect without the Cabinet’s signature, the Prime Minister’s countersignature and the Emperor’s promulgation.[73][74][75][76][77]

Supreme Court[edit]

The Supreme Court of Japan (最高裁判所) is the court of last resort and has the power of Judicial review; as defined by the Constitution to be «the court of last resort with power to determine the constitutionality of any law, order, regulation or official act».[78] The Supreme Court is also responsible for nominating judges to lower courts and determining judicial procedures. It also oversees the judicial system, overseeing activities of public prosecutors, and disciplining judges and other judicial personnel.[79]

High Courts[edit]

The High Courts of Japan (高等裁判所) has the jurisdiction to hear appeals to judgments rendered by District Courts and Family Courts, excluding cases under the jurisdiction of the Supreme Court. Criminal appeals are directly handled by the High Courts, but Civil cases are first handled by District Courts. There are eight High Courts in Japan: the Tokyo, Osaka, Nagoya, Hiroshima, Fukuoka, Sendai, Sapporo, and Takamatsu High Courts.[79]

Penal system[edit]

The Penal system of Japan (矯正施設) is operated by the Ministry of Justice. It is part of the criminal justice system, and is intended to resocialize, reform, and rehabilitate offenders. The ministry’s Correctional Bureau administers the adult prison system, the juvenile correctional system, and three of the women’s guidance homes,[80] while the Rehabilitation Bureau operates the probation and the parole systems.[81]

Other government agencies[edit]

The Cabinet Public Affairs Office’s Government Directory also listed a number of government agencies that are more independent from executive ministries.[82] The list for these types of agencies can be seen below.

- Japan National Tourism Organisation (JNTO)

- Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA)

- Japan External Trade Organisation (JETRO)

- The Japan Foundation

- Bank of Japan

- Japan Mint

- National Research Bureau of Brewing (NRIB)

- State Guest Houses (Akasaka Palace, Kyoto State Guest House)

- National Archives of Japan

- National Women’s Education Centre

- Japan Broadcasting Corporation (NHK)

- National Institutes for Cultural Heritage

- Japan Arts Council

- Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS)

- Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA)

- Japan Science and Technology Agency (JST)

- Japan Agency for Marine-Earth Science and Technology (JAMSTEC)

- National Institute for Materials Science (JIMS)

- Japan Atomic Energy Agency (JAEA)

- New Energy and Industrial Technology Development Organisation (NEDO)

- National Institute of Infectious Diseases (NIID)

- The Japan Institute for Labour Policy and Training

Local government[edit]

According to Article 92 of the Constitution, the local governments of Japan (地方公共団体) are local public entities whose body and functions are defined by law in accordance with the principle of local autonomy.[83][84] The main law that defines them is the Local Autonomy Law.[85][86] They are given limited executive and legislative powers by the Constitution. Governors, mayors and members of assemblies are constitutionally elected by the residents.

The Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications intervenes significantly in local government, as do other ministries. This is done chiefly financially because many local government jobs need funding initiated by national ministries. This is dubbed as the «thirty-percent autonomy».[87]

The result of this power is a high level of organizational and policy standardization among the different local jurisdictions allowing them to preserve the uniqueness of their prefecture, city, or town. Some of the more collectivist jurisdictions, such as Tokyo and Kyoto, have experimented with policies in such areas as social welfare that later were adopted by the national government.[87]

[edit]

Japan is divided into forty-seven administrative divisions, the prefectures are: one metropolitan district (Tokyo), two urban prefectures (Kyoto and Osaka), forty-three rural prefectures, and one «district», Hokkaidō. Large cities are subdivided into wards, and further split into towns, or precincts, or subprefectures and counties.

Cities are self-governing units administered independently of the larger jurisdictions within which they are located. In order to attain city status, a jurisdiction must have at least 500,000 inhabitants, 60 percent of whom are engaged in urban occupations. There are self-governing towns outside the cities as well as precincts of urban wards. Like the cities, each has its own elected mayor and assembly. Villages are the smallest self-governing entities in rural areas. They often consist of a number of rural hamlets containing several thousand people connected to one another through the formally imposed framework of village administration. Villages have mayors and councils elected to four-year terms.[88][89]

Structure[edit]

Each jurisdiction has a chief executive, called a governor (知事, chiji) in prefectures and a mayor (市町村長, shichōsonchō) in municipalities. Most jurisdictions also have a unicameral assembly (議会, gikai), although towns and villages may opt for direct governance by citizens in a general assembly (総会, sōkai). Both the executive and assembly are elected by popular vote every four years.[90][91][92]

Local governments follow a modified version of the separation of powers used in the national government. An assembly may pass a vote of no confidence in the executive, in which case the executive must either dissolve the assembly within ten days or automatically lose their office. Following the next election, however, the executive remains in office unless the new assembly again passes a no confidence resolution.[85]

The primary methods of local lawmaking are local ordinance (条例, jōrei) and local regulations (規則, kisoku). Ordinances, similar to statutes in the national system, are passed by the assembly and may impose limited criminal penalties for violations (up to 2 years in prison and/or 1 million yen in fines). Regulations, similar to cabinet orders in the national system, are passed by the executive unilaterally, are superseded by any conflicting ordinances, and may only impose a fine of up to 50,000 yen.[88]

Local governments also generally have multiple committees such as school boards, public safety committees (responsible for overseeing the police), personnel committees, election committees and auditing committees.[93] These may be directly elected or chosen by the assembly, executive or both.[87]

Scholars have noted that political contestations at the local level tend not to be marked by strong party affiliation or political ideologies when compared to the national level. Moreover, in many local communities candidates from different parties tend to share similiar concerns, e.g., regarding depopulation and how to attract new residents. Analyzing the political discourse among local politicians, Hijino suggests that local politics in depopulated areas is marked by two overarching ideas: «populationism» and «listenism.» He writes, «“Populationism” assumes the necessity of maintaining and increasing the number of residents for the future and vitality of the municipality. “Listenism” assumes that no decision can be made unless all parties are consulted adequately, preventing majority decisions taken by elected officials over issues contested by residents. These two ideas, though not fully-fledged ideologies, are assumptions guiding the behavior of political actors in municipalities in Japan when dealing with depopulation.»[94]

All prefectures are required to maintain departments of general affairs, finance, welfare, health, and labor. Departments of agriculture, fisheries, forestry, commerce, and industry are optional, depending on local needs. The Governor is responsible for all activities supported through local taxation or the national government.[87][91]

See also[edit]

- Japanese honours system

- Politics of Japan

References[edit]

- ^ «The World Factbook Japan». Central Intelligence Agency. Retrieved 5 September 2015.

- ^ «Article 4(1), Section 1». Constitution of Japan. 1947. Retrieved 5 September 2015.

- ^ a b «Article 65, Section 5». Constitution of Japan. 1947. Retrieved 5 September 2015.

- ^ a b c «Article 68(1), Section 5». Constitution of Japan. 1947. Retrieved 5 September 2015.

- ^ a b «Article 67(1), Section 5». Constitution of Japan. 1947. Retrieved 5 September 2015.

- ^ a b «Article 6(1), Section 1». Constitution of Japan. 1947. Retrieved 5 September 2015.

- ^ a b c «Article 1, Section 1». Constitution of Japan. 1947. Retrieved 5 September 2015.

- ^ a b «Article 76(2), Section 6». Constitution of Japan. 1947. Retrieved 5 September 2015.

- ^ Chaurasla, Radhey Shyam (2003). History of money. New Delhi: Atlantic Publishers and Distributors. p. 10. ISBN 9788126902286.

- ^ Koichi, Mori (December 1979). «The Emperor of Japan: A Historical Study in Religious Symbolism». Japanese Journal of Religious Studies. 6/4: 535–540.

- ^ Bob Tadashi, Wakabayashi (1991). «In Name Only: Imperial Sovereignty in Early Modern Japan». Journal of Japanese Studies. 7 (1): 25–57.

- ^ Satow, Ernest Mason (Aug 23, 2013). A Diplomat in Japan. Project Gutenberg. p. 282. Retrieved 5 September 2015.

- ^ «Asia’s First Parliament» (PDF). The New York Times. Retrieved 5 September 2015.

- ^ «The Nature of Sovereignty in Japan, 1870s–1920s» (PDF). University of Colorado Boulder. Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 September 2015. Retrieved 5 September 2015.

- ^ Lebra, Takie Sugiyama (1992). Japanese social organization (1 ed.). Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press. p. 51. ISBN 9780824814205.

- ^ «Article 34, Section 3». Constitution of the Empire of Japan. 1889. Retrieved 5 September 2015.

- ^ «Article 35, Section 3». Constitution of the Empire of Japan. 1889. Retrieved 5 September 2015.

- ^ Skya, Walter A. (2009). Japan’s holy war the ideology of radical Shintō ultranationalism. Durham: Duke University Press. p. 40. ISBN 9780822392460.

- ^ Martin, Bernd (2006). Japan and Germany in the modern world (1. paperback ed.). New York [u.a.]: Berghahn Books. p. 31. ISBN 9781845450472.

- ^ «The Constitution: Context and History» (PDF). Hart Publishing. Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 5 September 2015.

- ^ «Japan’s analog government struggles to accept anything online». Nikkei. Archived from the original on 18 June 2020. Retrieved 18 June 2020.

- ^ «Japan appoints ‘minister of loneliness’ to help people home alone». Nikkei. February 13, 2021. Archived from the original on February 23, 2021.

- ^ «Article 4, Section 1». Constitution of Japan. 1947. Retrieved 5 September 2015.

- ^ «Did the Emperor of Japan really fall from being a ruler to a symbol» (PDF). Tsuneyasu Takeda. Instructor, Keio University. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 February 2019. Retrieved 28 August 2015.

- ^ «2009 Japanese Emperor and Empress Visited in Vancouver». YouTube. Archived from the original on 2014-06-07. Retrieved 18 June 2015.

- ^ «A shadow of a shogun». The Economist. 2012. Retrieved 18 June 2015.

- ^ «Fundamental Structure of the Government of Japan». Prime Minister’s Official Residence Website. Retrieved 1 September 2015.

- ^ «Article 5, Section 1». Constitution of Japan. 1947. Retrieved 5 September 2015.

- ^ «最高裁判所判例集 事件番号 平成1(行ツ)126». Courts in Japan. Retrieved August 10, 2020.

- ^ «Japan’s royal family pose for unusual New Year photo». The Daily Telegraph. 2014. Archived from the original on 2022-01-12. Retrieved 18 June 2015.

- ^ Kitagawa, Joseph M. (1987). On understanding Japanese religion. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press. p. 145. ISBN 9780691102290.

- ^ Smith, Robert J. (1974). Ancestor worship in contemporary Japan ([Repr.]. ed.). Stanford, Calif.: Stanford University Press. pp. 8–9. ISBN 9780804708739.

- ^ «Kojiki». Ō no Yasumaro. Archived from the original on 30 April 2020. Retrieved 5 September 2015.

- ^ «Nihon Shoki» (PDF). Prince Toneri. Retrieved 5 September 2015.

- ^ «Enthronement and Ceremonies». Imperial Household Agency. Retrieved 1 September 2015.

- ^ «The 20th Anniversary of His Majesty the Emperor’s Accession to the Throne». Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Retrieved 1 September 2015.

- ^ «Article 69, Section 5». Constitution of Japan. 1947. Retrieved 5 September 2015.

- ^ «Article 72, Section 5». Constitution of Japan. 1947. Retrieved 5 September 2015.

- ^ a b c «Article 7, Section 1». Constitution of Japan. 1947. Retrieved 5 September 2015.

- ^ a b «Article 67(2), Section 5». Constitution of Japan. 1947. Retrieved 5 September 2015.

- ^ a b «Article 63, Section 4». Constitution of Japan. 1947. Retrieved 5 September 2015.

- ^ «Article 66(2), Section 5». Constitution of Japan. 1947. Retrieved 5 September 2015.

- ^ «内閣法». Government of Japan. Archived from the original on 25 April 2010. Retrieved 1 September 2015.

- ^ «Toshiaki Endo appointed Olympics minister». The Japan Times. Retrieved 1 September 2015.

- ^ «Article 68, Section 5». Constitution of Japan. 1947. Retrieved 5 September 2015.

- ^ «Article 68(2), Section 5». Constitution of Japan. 1947. Retrieved 5 September 2015.

- ^ «Article 75». Constitution of Japan. 1947. Retrieved 5 September 2015.

- ^ «List of Ministers». Prime Minister’s Office of Japan. 13 September 2023. Retrieved 15 September 2023.

- ^ «Bureaucrats of Japan». Library of Congress Country Studies. Retrieved 1 September 2015.

- ^ «Government directory.» Tokyo: Cabinet Public Affairs Office, Cabinet Secretariat. Retrieved from https://www.japan.go.jp/directory/index.html.

- ^ «Article 43(1), Section 4». Constitution of Japan. 1947. Retrieved 5 September 2015.

- ^ «Article 96, Section 9». Constitution of Japan. 1947. Retrieved 5 September 2015.

- ^ «Article 64(1), Section 4». Constitution of Japan. 1947. Retrieved 5 September 2015.

- ^ a b c «Diet enacts law lowering voting age to 18 from 20». The Japan Times. Retrieved 18 June 2015.

- ^ «Article 56(1), Section 4». Constitution of Japan. 1947. Retrieved 5 September 2015.

- ^ «Article 55, Section 4». Constitution of Japan. 1947. Retrieved 5 September 2015.

- ^ «Article 53, Section 4». Constitution of Japan. 1947. Retrieved 5 September 2015.

- ^ a b «Article 54(2), Section 4». Constitution of Japan. 1947. Retrieved 5 September 2015.

- ^ «Article 45, Section 4». Constitution of Japan. 1947. Retrieved 5 September 2015.

- ^ a b «解散と万歳». Parti démocrate du Japon. Retrieved 1 September 2015.

- ^ Japanese PM dissolves lower house of parliament, calls snap elections 일본 중의원 해, journal télévisé, Arirang News, 21 novembre 2014 — une partie des phases et éléments la cérémonie peut être vue en arrière-plan

- ^ «小泉進次郎氏、衆議院解散でも万歳しなかった「なぜ今、解散か」». The Huffington Post. Retrieved 1 September 2015.

- ^ «開会式». House of Councillors. Retrieved 1 September 2015.

- ^ «Overview of the Judicial System in Japan». Supreme Court of Japan. Retrieved 18 June 2015.

- ^ «Article 76, Section 6». Constitution of Japan. 1947. Retrieved 5 September 2015.

- ^ a b «Article 78, Section 6». Constitution of Japan. 1947. Retrieved 5 September 2015.

- ^ «Article 79(2), Section 6». Constitution of Japan. 1947. Retrieved 5 September 2015.

- ^ «Article 82(2), Section 6». Constitution of Japan. 1947. Retrieved 5 September 2015.

- ^ «Change at the top court’s helm». The Japan Times. Retrieved 18 June 2015.

- ^ Dean, Meryll (2002). Japanese legal system : text, cases & materials (2nd ed.). London: Cavendish. pp. 55–58. ISBN 9781859416730.

- ^ a b «Japanese Civil Code». Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 18 June 2015.

- ^ «MacArthur and the American Occupation of Japan». Archived from the original on 21 March 2017. Retrieved 18 June 2015.

- ^ «Article 74, Section 5». Constitution of Japan. 1947. Retrieved 5 September 2015.

- ^ «Article 7(1), Section 1». Constitution of Japan. 1947. Retrieved 5 September 2015.

- ^ «II. The law-making process». Cabinet Legislation Bureau. Retrieved 6 September 2015.

- ^ «The Privy Seal and State Seal». Imperial Household Agency. Retrieved 6 September 2015.

- ^ «Promulgation of Laws». National Printing Bureau. Retrieved 6 September 2015.

- ^ «Article 81, Section 6». Constitution of Japan. 1947. Retrieved 5 September 2015.

- ^ a b «Overview of the Judicial System in Japan». Supreme Court of Japan. Retrieved 6 September 2015.[dead link]

- ^ «Correction Bureau». Ministry of Justice. Retrieved 6 September 2015.

- ^ «Rehabilitation Bureau». Ministry of Justice. Retrieved 6 September 2015.

- ^ «Government Directory». Tokyo: Cabinet Public Affairs Office, Cabinet Secretariat. Retrieved (23 August 2022) from https://www.japan.go.jp/directory/index.html.

- ^ «Article 92, 93, 94 and 95, Section 8». Constitution of Japan. 1947. Retrieved 5 September 2015.

- ^ «Final Report» (PDF). Research Commission on the Constitution House of Representatives, Japan. Retrieved September 3, 2020. p463-480

- ^ a b «AUTHORITY OF THE NATIONAL AND LOCAL GOVERNMENTS UNDER THE CONSTITUTION». Duke University School of Law. Retrieved 6 September 2015.

- ^ «地方自治法について» (PDF). Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications. Retrieved August 22, 2020.

- ^ a b c d 三割自治 «Local Government». Retrieved 18 June 2015.

- ^ a b «Local Autonomy Law». Government of Japan. Archived from the original on 9 February 2018. Retrieved 6 September 2015.

- ^ «The Large City System of Japan» (PDF). National Graduate Institute for Policy Studies. Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 September 2019. Retrieved 6 September 2015.

- ^ «Article 93(2), Section 8». Constitution of Japan. 1947. Retrieved 5 September 2015.

- ^ a b «Local Autonomy in Japan Current Situation & Future Shape» (PDF). Council of Local Authorities for International Relations. Retrieved 6 September 2015.

- ^ «An Outline of Local Government in Japan» (PDF). Council of Local Authorities for International Relations. Retrieved 6 September 2015.

- ^ «The Organization of Local Government Administration in Japan» (PDF). National Graduate Institute for Policy Studies. Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 March 2016. Retrieved 6 September 2015.

- ^ Hijino, Ken Victor Leonard (2023-03-27). «The politics of depopulation in Japanese municipalities: Ideas and underlying ideologies». Contemporary Japan: 1–22. doi:10.1080/18692729.2023.2191478. ISSN 1869-2729.

External links[edit]

- Background notes of the US Department of State, Japan’s Government

- Search official Japanese Government documents and records

- Facts about Japan by CIA’s The World Factbook

- Video of the Enthronement Ceremony of the Emperor

- Video of the National Diet Convocation Ceremony

- Video of the House of Representatives Dissolution Ceremony

- Works by Government of Japan at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

Фумио Кисида. Фото: Zhang Xiaoyu / Xinhua / Reuters

Премьер-министр Японии Фумио Кисида объявил новый состав правительства страны. Об этом сообщает «Интерфакс».

Свои посты сохранили генеральный секретарь правительства Хирокадзу Мацуно, министр иностранных дел Есимасу Хаяси, министр финансов Сюнъити Судзуки, министр государственных земель, транспорта, инфраструктуры и туризма Тэцуо Сайто.

Министром обороны стал уже занимавший эту должность с 2008 по 2009 год Ясукадзу Хамада. Экс-глава Минобороны Нобуо Киси стал советником премьер-министра по вопросам национальной безопасности. Главой министерства экономической безопасности был назначен председатель политического совета правящей Либерально-демократической партии Санаэ Такаити.

Должность министра цифровизации получил Таро Коно, занимавший пост главы министерства иностранных дел с 2017 по 2019 год. Министром экономики, торговли и промышленности, а также министром, ответственным за экономическое сотрудничество с Россией, в одном лице стал экс-глава Минэкономразвития страны Ясутоси Нисимура. До этого он также отвечал за борьбу с COVID-19.

Главой Минздрава стал Кацунобу Като, пост министра юстиции занял Ясухиро Ханаси, министром образования стал Кэйко Нагаока. Министерство сельского, лесного и рыбного хозяйства было поручено возглавить Тэцуо Номуре.

10 августа премьер-министр Японии Фумио Кисида сообщил, что правительство Японии в полном составе ушло в отставку. О желании Кисиды обновить кабмин сообщалось еще прошлой осенью. Тогда он заявлял, что руководству страны необходимо «встретиться лицом к лицу с общественным мнением».

В Японии новый глава правительства – Фумио Кисида. Ждать ли внешнеполитических перемен от нового премьер-министра? Изменится ли курс Токио на фоне американо-китайского противостояния? Кем считают сейчас Россию в Японии: соперником, партнёром, противником? Об этом Фёдор Лукьянов поговорил с Тэцуо Котани, ведущим научным сотрудником Японского института международных отношений, специально для передачи «Международное обозрение».

– Господин Котани, ждать ли внешнеполитических перемен от нового премьер-министра Японии?

– Господин Кисида победил на выборах лидера партии благодаря поддержке бывшего премьер-министра Синдзо Абэ. Абэ ещё в прошлом году, уходя в отставку, хотел, чтобы Кисида стал его преемником. Поэтому внешнеполитическая линия будет продолжением политики Абэ. За одним исключением – Россия.

– Отчего же? Россия была как раз важной частью курса Абэ.

– Господин Абэ был выдающимся премьер-министром, его очень высоко оценивают. Но, по общему мнению, он допустил одну ошибку. И это была политика в отношении России – она не привела ни к какому результату. Поэтому ожидать её продолжения не надо.

– Ну допустим. И кем Россию считают сейчас в Японии: соперником, партнёром, противником?

– При премьер-министре Абэ Россию определили как стратегического партнёра в деле решения различных региональных проблем. Но такой статус был основан на предположении, что мы и дальше работаем над договорённостью по территориальному вопросу. Сейчас есть консенсусное мнение, что подход Абэ к России не сработал. И новое руководство не видит в России стратегического партнёра.

Но мы не считаем Россию и врагом. Главное для Японии – российско-китайские отношения. Как далеко зайдёт партнёрство Москвы и Пекина? Мы определяем Россию как возможного партнёра нашего стратегического противника.

– Давайте как раз и перейдём к стратегическому соперничеству. Азиатско-Тихоокеанский (а сейчас чаще говорят – Индо-Тихоокеанский регион) становится центром стратегических перемен, всё очень подвижно. Но японская линия, кажется, стабильна, по сути, подходы сохраняются с середины прошлого века. Могут ли начаться кардинальные изменения?

– Не соглашусь с вами. Япония сильно изменилась после холодной войны. После Второй мировой внешняя политика определялась как пацифизм в рамках одной нации. Другими словами, каков бы ни был потенциал Японии, её не интересует, что происходит за её пределами. Внешняя политика была очень реактивной. Сейчас Токио проактивен, выдвигает различные региональные и даже глобальные инициативы. Например, концепция «Свободного и открытого Индо-Тихоокеанского региона». Это именно Япония предложила в 2016 г., а сегодня Соединённые Штаты, Австралия, Индия, Азия и европейские страны используют тот термин. Абэ говорил, что внешняя политика Японии должна вносить активный вклад в дело мира, и это пользуется общественной поддержкой. Так что мы меняемся.

– Хорошо, но мы видим, что в этой части мира происходит милитаризация, чего Япония прежде старалась избегать. Это тоже изменится?

– Япония предпочла бы по-прежнему полагаться на региональное партнёрство, дипломатию и экономику, а не на военную силу. Но надо смотреть в глаза реальности. Вот, например, тайваньский вопрос. Там в случае обострения не будет выбора, какие средства использовать. И Япония должна обладать соответствующими возможностями. Япония сегодня понимает важность военной мощи, в том числе для реализации нашего видения свободного и открытого пространства. И это одна из причин, почему в 2015 г. Япония приняла Закон о мире и безопасности, согласно которому она может принимать меры по коллективной самообороне.

– Только что в Вашингтоне прошла первая встреча в верхах группы QUAD – США, Индия, Япония и Австралия. Это прообраз военного альянса?

– QUAD изначально был ориентирован на создание рамочных условий для безопасности, это идея премьер-министра Абэ. Но, с нашей точки зрения, QUAD шире и важнее, чем просто структура безопасности. Потому что он обладает потенциалом для обеспечения региона важными общественными благами. Например, одно из направлений – снабжение всего региона, особенно Юго-Восточной Азии, вакцинами. Или совместные действия против климатических изменений. Я думаю, что деятельность, менее связанная с военной безопасностью, перспективна и пользуется поддержкой во всех четырёх странах.

– Но китайско-американское противостояние обостряется. И естественно ожидать, что американцы захотят привлечь на помощь партнёров в регионе.

– QUAD – неподходящая основа для военного сотрудничества, которого хотели бы Соединённые Штаты. И это одна из причин, почему США сформировали AUKUS с Великобританией и Австралией без Японии и Индии.

Индия, например, весьма неохотно идёт на военное взаимодействие с другими странами, если оно подразумевает что-то большее, чем совместные морские учения. Не думаю, что США рассчитывают на превращение QUAD в военный альянс. Они будут по-разному работать с разными союзниками.

– В Европе растут сомнения относительно незыблемости союзнических обязательств США. Звучат разговоры о европейской стратегической автономии. Конечно, Тихоокеанский регион в другом положении, он как раз становится для США большим приоритетом, чем Атлантика. И всё же – в Японии нет опасений, что американцы откажутся от своих гарантий?

– Принципиальная разница между Европой и Азией в том, что у европейцев есть НАТО, а у азиатов нет. Европейские страны, возможно, способны обеспечить себе автономию от Соединённых Штатов, союзники США в Азии такой роскоши себе позволить не могут. Наш план «Б» – это продолжение плана «A».

Есть глубокие двусторонние отношения с Соединёнными Штатами – у Японии, Кореи, Австралии, Филиппин. И все мы заинтересованы в том, чтобы их сохранять и укреплять. Поэтому поворот Байдена к Азии нас устраивает. Как и общее изменение американского подхода – меньше роли глобального полицейского и концентрация на конкретных задачах, особенно в Азии.

Не только Япония, но и другие союзники США будут стараться создать партнёрскую сеть, удобную Соединённым Штатам.

В Азии, конечно, понимают, что по мере роста мощи Китая возможности США гарантировать безопасность всем азиатским союзникам будут уменьшаться. Поэтому они стараются работать совместно над повышением своих возможностей. QUAD – хороший пример партнёрской сети безопасности, AUKUS – тоже. Но повторю – плана «Б», как обойтись без американцев в сфере безопасности, у нас нет.

– Можете ли вы представить себе обстоятельства, при которых Япония пересмотрит свою политику не приобретать ядерное оружие?

– Среди японской общественности очень сильны антиядерные настроения – по понятным причинам. Но политическое решение не иметь ядерного оружия связано не с общественным мнением, а со стратегическими расчётами. А именно: ядерный статус сам по себе не отвечает стратегическим интересам Японии. Конечно, если ситуация кардинально изменится, Япония может пересмотреть позицию относительно ядерного оружия. Ключевое обстоятельство – сохранение Соединёнными Штатами ядерного зонтика над Японией. Если по каким-то причинам американские гарантии перестанут действовать, нам придётся задуматься о том, чтобы самим стать ядерными.

Телепередача «Международное обозрение» выходит по пятницам с 13 марта 2015 г. на канале «Россия-24». Это продолжение тележурнала «Международная панорама», который в СССР смотрели по воскресеньям. Больше информации здесь.

Правительство Японии в полном составе ушло в отставку на фоне перестановок. Действующий премьер Фумио Кисида уже назначил новых глав МИД, Минобороны и других министров в ходе формирования нового состава Кабмина. Об этом сообщило агентство Kyodo.

Его структура осталась прежней, как и руководящий состав возглавляемой Кисидой правящей Либерально-демократической партии (ЛДП). Генсек Кабмина Хирокадзу Мацуно, озвучивший изменения в правительстве, также сохранил свой пост.

МИД Японии возглавила 70-летняя экс-министр юстиции Ёко Камикава, она сменила Ёсимасу Хаяси, занимавшего этот пост с 2021 года. А новым главой Минобороны назначен 54-летний Минору Кихара. Он успел побывать советником премьер-министра по вопросам национальной безопасности, парламентским замминистра обороны и замминистра финансов.

Произошли и другие кадровые изменения. Так, новым министром по административным делам и коммуникациям стал Дзюндзи Судзуки, пост министра юстиции достался Рюдзи Коидзуми, министром по восстановлению экономики назначен Ёситака Синдо, министром образования, культуры, спорта, науки и технологий — Масахито Морияма. Министром сельского, лесного и рыбного хозяйства стал Итиро Миясита, председателем Национальной комиссии общественной безопасности — Ёсифуми Мацумура, министром охраны окружающей среды — Синтаро Ито, министром здравоохранения, труда и благосостояния — Кэйдзо Такэми.

Число женщин-министров впервые дошло до пяти. Кроме Камикавы и Такаити это Аюко Като — министр по проблемам низкой рождаемости, Синако Цутия — министр по делам реконструкции и Ханако Дзими — министр регионального развития. Последняя будет ещё и министром по делам Окинавы и «северных территорий» (так в Японии называют российские Южные Курильские острова).

Сохранили свои посты министр финансов Сюнъити Судзуки, министр экономической безопасности Санаэ Такаити, министр по делам цифровизации Таро Коно и министр экономики, торговли и промышленности Ясутоси Нисимура. Как считают аналитики, премьер-министр попытался сбалансировать интересы всех партийных фракций, чтобы успешно переизбраться в следующем году на пост председателя ЛДП, а значит, и премьер-министра Японии.

А ранее премьер-министр страны Фумио Кисида заявил, что осенью Япония проведёт онлайн-саммит «Группы семи». В 2023 году Токио председательствует в G7.

Ниже представлен список премьер-министров Японии с момента учреждения этого поста в 1885 году до настоящего времени. Указаны также исполняющие обязанности премьер-министра.

Первая цифра обозначает порядковый номер кабинета, а вторая — порядковый номер премьер-министра. Цвета строк соответствуют политическим партиям, выдвинувшим его кандидатуру.

Обратите внимание: в целях унификации все имена в списке приводятся в «европейском» порядке — имя, потом фамилия.

| Содержание:

|

Эпоха Мэйдзи (1868—1912) Примечания • Ссылки |

|---|

| К# | М# | Портрет | Имя | Начало полномочий | Окончание полномочий | Партия |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

||||||

| 1 | 1 |  |

Хиробуми Ито (1841—1909) (первый срок) |

22 декабря 1885 | 30 апреля 1888 | нет |

| 2 | 2 |  |

Киётака Курода (1840—1900) |

30 апреля 1888 | 25 октября 1889[1] | нет |

| — | — |  |

Санэтоми Сандзё[2] (1837—1891) |

25 октября 1889 | 24 декабря 1889 | нет |

| Принятие Конституции Японской империи | ||||||

| 3 | 3 |  |

Аритомо Ямагата (1838—1922) (первый срок) |

24 декабря 1889 | 6 мая 1891 | нет |

| 4 | 4 |  |

Масаёси Мацуката (1835—1924) (первый срок) |

6 мая 1891 | 8 августа 1892 | нет |

| 5 | — |  |

Хиробуми Ито (1841—1909) (второй срок) |

8 августа 1892 | 31 августа 1896 [3] | нет |

| В течение этого периода обязанности премьер-министра исполнял глава Тайного Совета Киётака Курода. | ||||||

| 6 | — |  |

Масаёси Мацуката (1835—1924) (второй срок) |

18 сентября 1896 | 12 января 1898 | нет |

| 7 | — |  |

Хиробуми Ито (1841—1909) (третий срок) |

12 января 1898 | 30 июня 1898 | нет |

| 8 | 5 |  |

Сигэнобу Окума (1838—1922) (первый срок) |

30 июня 1898 | 8 ноября 1898 | Кэнсэйто |

| 9 | — |  |

Аритомо Ямагата (1838—1922) (второй срок) |

8 ноября 1898 | 19 октября 1900 | нет |

| 10 | — |  |

Хиробуми Ито (1841—1909) (четвертый срок) |

19 октября 1900 | 10 мая 1901 [3] | Риккэн Сэйюкай |

| В течение этого периода обязанности премьер-министра исполнял глава Тайного Совета Киммоти Сайондзи. | ||||||

| 11 | 6 |  |

Таро Кацура (1848—1913) (первый срок) |

2 июня 1901 | 7 января 1906 | нет (Генерал в отставке) |

| 12 | 7 |  |

Киммоти Сайондзи (1849—1940) (первый срок) |

7 января 1906 | 14 июля 1908 | Риккэн Сэйюкай |

| 13 | — |  |

Таро Кацура (1848—1913) (второй срок) |

14 июля 1908 | 30 августа 1911 | нет (Генерал в отставке) |

| 14 | — |  |

Киммоти Сайондзи (1849—1940) (второй срок) |

30 августа 1911 | 21 декабря 1912 | Риккэн Сэйюкай |

|

||||||

| 15 | — |  |

Таро Кацура (1848—1913) (третий срок) |

21 декабря 1912 | 20 февраля 1913 | нет (Генерал в отставке) |

| 16 | 8 |  |

Гомбэй Ямамото (1852—1933) (первый срок) |

20 февраля 1913 | 16 апреля 1914 | Военный (Флот) |

| 17 | — |  |

Сигэнобу Окума (1838—1922) (второй срок) |

16 апреля 1914 | 9 октября 1916 | Риккэн Досикай |

| 18 | 9 |  |

Масатакэ Тэраути (1852—1919) |

9 октября 1916 | 29 сентября 1918 | Военный (Армия) |

| 19 | 10 |  |

Такаси Хара (1856—1921) |

29 сентября 1918 | 4 ноября 1921 [4] | Риккэн Сэйюкай (Член Национального Совета) |

| В течение этого периода обязанности премьер-министра исполнял министр иностранных дел Косай Утида. | ||||||

| 20 | 11 |  |

Корэкиё Такахаси (1854—1936) |

13 ноября 1921 | 12 июня 1922 | Риккэн Сэйюкай |

| 21 | 12 |  |

Томосабуро Като (1861—1923) |

12 июня 1922 | 24 августа 1923[5] | Военный (Флот) |

| В течение этого периода обязанности премьер-министра исполнял министр иностранных дел Косай Утида. | ||||||

| 22 | — |  |

Гомбэй Ямамото (1852—1933) (второй срок) |

2 сентября 1923 | 7 января 1924 | Военный (Флот) |

| 23 | 13 |  |

Кэйго Киёура (1850—1942) |

7 января 1924 | 11 июня 1924 | нет |

| 24 | 14 |  |

Такааки Като (1860—1926) |

11 июня 1924 | 2 августа 1925 [6] | Кэнсэйто, Риккэн Сэйюкай и Клуб Какусин |

| 2 августа 1925 | 28 января 1926[5] | Кэнсэйто | ||||

| В течение этого периода обязанности премьер-министра исполнял министр внутренних дел Рэйдзиро Вакацуки. | ||||||

| 25 | 15 |  |

Рэйдзиро Вакацуки (1866—1949) (первый срок) |

30 января 1926 | 20 апреля 1927 | Кэнсэйто |

|

||||||

| 26 | 16 |  |

Гиити Танака (1864—1929) |

20 апреля 1927 | 2 июля 1929 | Риккэн Сэйюкай (Генерал в отставке) |

| 27 | 17 |  |

Осати Хамагути (1870—1931) |

2 июля 1929 | 14 апреля 1931[7] | Риккэн Минсэйто |

| 28 | — |  |

Рэйдзиро Вакацуки (1866—1949) (второй срок) |

14 апреля 1931 | 13 декабря 1931 | Риккэн Минсэйто |

| 29 | 18 |  |

Цуёси Инукай (1855—1932) |

13 декабря 1931 | 16 мая 1932[4] | Риккэн Сэйюкай |

| В течение этого периода обязанности премьер-министра исполнял министр финансов Такахаси Корэкиё. | ||||||

| 30 | 19 |  |

Макото Сайто (1858—1936) |

26 мая 1932 | 8 июля 1934 | Военный (Флот) |

| 31 | 20 |  |

Кэйсукэ Окада (1868—1952) |

8 июля 1934 | 9 марта 1936[8] | Военный (Флот) |

| 32 | 21 |  |

Коки Хирота (1878—1948) |

9 марта 1936 | 2 февраля 1937 | Нет |

| 33 | 22 |  |

Сэндзюро Хаяси (1876—1943) |

2 февраля 1937 | 4 июня 1937 | Военный (Армия) |

| 34 | 23 |  |

Фумимаро Коноэ (1891—1945) (первый срок) |

4 июня 1937 | 5 января 1939 | Нет |

| 35 | 24 |  |

Киитиро Хиранума (1867—1952) |

5 января 1939 | 30 августа 1939 | Нет |

| 36 | 25 |  |

Нобуюки Абэ (1875—1953) |

30 августа 1939 | 16 января 1940 | Военный (Армия) |

| 37 | 26 |  |

Мицумаса Ёнай (1880—1948) |

16 января 1940 | 22 июля 1940 | Военный (Флот) |

| 38 | — |  |

Фумимаро Коноэ (1891—1945) (второй срок) |

22 июля 1940 | 18 июля 1941 | Тайсэй Ёкусанкай |

| 39 | (третий срок) | 18 июля 1941 | 18 октября 1941 | |||

| 40 | 27 |  |

Хидэки Тодзио (1884—1948) |

18 октября 1941 | 22 июля 1944 | Военный (Армия) |

| 41 | 28 |  |

Куниаки Коисо (1880—1950) |

22 июля 1944 | 7 апреля 1945 | Военный (Армия) |

| 42 | 29 |  |

Кантаро Судзуки (1868—1948) |

7 апреля 1945 | 17 августа 1945 | Военный (Флот) |

| 43 | 30 |  |

Принц Нарухико Хигасикуни (1887—1990) |

17 августа 1945 | 9 октября 1945 | Императорская семья |

| 44 | 31 |  |

Кидзюро Сидэхара (1872—1951) |

9 октября 1945 | 22 мая 1946 | Нет |

| Принятие Конституции Японии | ||||||

| 45 | 32 |  |

Сигэру Ёсида (1878—1967) (первый срок) |

22 мая 1946 | 24 мая 1947 | Либеральная |

| 46 | 33 |  |

Тэцу Катаяма (1887—1978) |

24 мая 1947 | 10 марта 1948 | Социалистическая |

| 47 | 34 |  |

Хитоси Асида (1887—1959) |

10 марта 1948 | 15 октября 1948 | Демократическая |

| 48 | — |  |

Сигэру Ёсида (1878—1967) (второй срок) |

15 октября 1948 | 16 февраля 1949 | Либеральная |

| 49 | (третий срок) | 16 февраля 1949 | 30 октября 1952 | |||

| 50 | (четвертый срок) | 30 октября 1952 | 21 мая 1953 | |||

| 51 | (пятый срок) | 21 мая 1953 | 10 декабря 1954 | |||

| 52 | 35 |  |

Итиро Хатояма (1883—1959) (первый срок) |

10 декабря 1954 | 19 марта 1955 | Демократическая |

| 53 | (второй срок) | 19 марта 1955 | 22 ноября 1955 | |||

| 54 | (третий срок) | 22 ноября 1955 | 23 декабря 1956 | Либерально-демократическая | ||

| 55 | 36 |  |

Тандзан Исибаси (1884—1973) |

23 декабря 1956 | 25 февраля 1957[9] | Либерально-демократическая |

| 56 | 37 |  |

Нобусукэ Киси (1896—1987) (первый срок) |

25 февраля 1957 | 12 июня 1958 | Либерально-демократическая |

| 57 | (второй срок) | 12 июня 1958 | 19 июля 1960 | |||

| 58 | 38 |  |

Хаято Икэда (1899—1965) (первый срок) |

19 июля 1960 | 8 декабря 1960 | Либерально-демократическая |

| 59 | (второй срок) | 8 декабря 1960 | 9 декабря 1963 | |||

| 60 | (третий срок) | 9 декабря 1963 | 9 ноября 1964 | |||

| 61 | 39 |  |

Эйсаку Сато (1901—1975) (первый срок) |

9 ноября 1964 | 17 февраля 1967 | Либерально-демократическая |

| 62 | (второй срок) | 17 февраля 1967 | 14 января 1970 | |||

| 63 | (третий срок) | 14 января 1970 | 7 июля 1972 | |||

| 64 | 40 |  |

Какуэй Танака (1918—1993) (первый срок) |

7 июля 1972 | 22 декабря 1972 | Либерально-демократическая |

| 65 | (второй срок) | 22 декабря 1972 | 9 декабря 1974 | |||

| 66 | 41 |  |

Такэо Мики (1907—1988) |

9 декабря 1974 | 24 декабря 1976 | Либерально-демократическая |

| 67 | 42 |  |

Такэо Фукуда (1905—1995) |

24 декабря 1976 | 7 декабря 1978 | Либерально-демократическая |

| 68 | 43 |  |

Масаёси Охира (1910—1980) (первый срок) |

7 декабря 1978 | 9 ноября 1979 | Либерально-демократическая |

| 69 | (второй срок) | 9 ноября 1979 | 12 июня 1980 [5] | |||

| В течение этого периода обязанности премьер-министра исполнял Генеральный секретарь кабинета Масаёси Ито. | ||||||

| 70 | 44 |  |

Дзэнко Судзуки (1911—2004) |

17 июля 1980 | 27 ноября 1982 | Либерально-демократическая |

| 71 | 45 |  |

Ясухиро Накасонэ (1918) (первый срок) |

27 ноября 1982 | 27 декабря 1983 | Либерально-демократическая |

| 72 | (второй срок) | 27 декабря 1983 | 22 июля 1986 | |||

| 73 | (третий срок) | 22 июля 1986 | 6 ноября 1987 | |||

| 74 | 46 |  |

Нобору Такэсита (1924–2000) |

6 ноября 1987 | 3 июня 1989 | Либерально-демократическая |

|

||||||

| 75 | 47 |  |

Сосукэ Уно (1922–1998) |

3 июня 1989 | 10 августа 1989 | Либерально-демократическая |

| 76 | 48 |  |

Тосики Кайфу (1931) (первый срок) |

10 августа 1989 | 28 февраля 1990 | Либерально-демократическая |

| 77 | (второй срок) | 28 февраля 1990 | 5 ноября 1991 | |||

| 78 | 49 |  |

Киити Миядзава (1919–2007) |

5 ноября 1991 | 9 августа 1993 | Либерально-демократическая |

| 79 | 50 |  |

Морихиро Хосокава (1938) |

9 августа 1993 | 28 апреля 1994 | Новая Япония |

| 80 | 51 |  |

Цутому Хата (1935) |

28 апреля 1994 | 30 июня 1994 | Партия обновления |

| 81 | 52 |  |

Томиити Мураяма (1924) |

30 июня 1994 | 11 января 1996 | Социалистическая |

| 82 | 53 |  |

Рютаро Хасимото (1937—2006) (первый срок) |

11 января 1996 | 7 ноября 1996 | Либерально-демократическая |

| 83 | (второй срок) | 7 ноября 1996 | 30 июля 1998 | |||

| 84 | 54 |  |

Кэйдзо Обути (1937–2000) |

30 июля 1998 | 5 апреля 2000[10] | Либерально-демократическая |

| 85 | 55 |  |

Ёсиро Мори (1937) (первый срок) |

5 апреля 2000 | 4 июля 2000 | Либерально-демократическая |

| 86 | (второй срок) | 4 июля 2000 | 26 апреля 2001 | |||

| 87 | 56 |  |

Дзюнъитиро Коидзуми (1942) (первый срок) |

26 апреля 2001 | 19 ноября 2003 | Либерально-демократическая |

| 88 | (второй срок) | 19 ноября 2003 | 21 сентября 2005 | |||

| 89 | (третий срок) | 21 сентября 2005 | 26 сентября 2006 | |||

| 90 | 57 |  |

Синдзо Абэ (1954) |

26 сентября 2006 | 26 сентября 2007 | Либерально-демократическая |

| 91 | 58 |  |

Ясуо Фукуда (1936) |

26 сентября 2007 | 24 сентября 2008 | Либерально-демократическая |

| 92 | 59 |  |

Таро Асо (1940) |

24 сентября 2008 | 19 сентября 2009 | Либерально-демократическая |

| 93 | 60 |  |

Юкио Хатояма (1947) |

16 сентября 2009 | 8 июня 2010 | Демократическая |

| 94 | 61 |  |

Наото Кан (1946) |

8 июня 2010 | 29 августа 2011 | Демократическая |

| 95 | 62 |  |

Ёсихико Нода (1957) |

30 августа 2011 | действующий премьер-министр | Демократическая |

Примечания

- ↑ После отставки правительства император принял отставку и пригласил главу Тайного Совета Сандзё Санэтоми возглавить правительство на несколько месяцев. Однако на сегодняшний день правительство Сандзё обычно рассматривается как продолжение правительства Куроды.

- ↑ И.о. премьер-министра, председатель Тайного Совета.

- ↑ 1 2 Ушел в отставку.

- ↑ 1 2 Убит.